From

Elizabeth Crawford's excellent introduction to our reprint edition:

Susan Alice Kerby was

the pen name of [Alice] Elizabeth Burton (1908-1990), who had been born in

Cairo, the daughter of Richard Burton (c.1879-c.1908). He was probably English,

while his wife Alice (1884-1962 née Kerby) was Canadian. The couple had married

in Chicago in 1907. It is to be presumed that Richard Burton died around the

time of Elizabeth’s birth because after returning from Egypt to her home town,

Windsor, Ontario, Alice was described as Burton’s widow when she remarried in

October 1909.

We first catch a glimpse of Elizabeth Burton in 1926 when,

described as a student, she sailed, unaccompanied, from Naples to the USA after

spending time in Rome, where she had stayed with an aunt and studied music and

history. In 1929, still a student, she again paid a visit to Europe, perhaps

visiting English relatives. Back in

Canada she launched her career as a journalist and over the next few years

worked in radio and in advertising. In 1935 she again spent some time in

England, arriving back in Canada in June and then in November, in Windsor,

married John Aitken, a fellow journalist. However, the marriage seems to have

been short lived; Elizabeth later recorded that in 1936 she decided to move to

England. At some point there was a divorce and in 1950 Elizabeth changed her

name by deed poll from ‘Aitken’ back to ‘Burton’. However, she maintained her

link with Canada, acting as the London correspondent of the Windsor Star from 1945-1965.

…

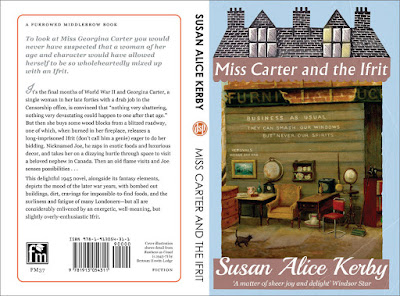

Elizabeth Burton’s first novel, Cling to Her, Waiting, written under her own name, was published in

the autumn of 1939 and her second, A

Fortnight at Frascati, for which she used the ‘Susan Alice Kerby’ pen name,

appeared in 1940. There was then a five-year gap until the publication of Miss Carter and the Ifrit in 1945,

suggesting that in the interim she was engaged on wartime business with little

time to write novels. Miss Carter worked ‘in Censorship’ but there is no

evidence to tell us how Elizabeth Burton was employed, although it was possibly

in some similar capacity.

Thanks

to Elizabeth, as always, for unearthing such wonderful tidbits for her intros.

Some choice snippets from

a review of Miss Carter and the Ifrit

in the Windsor Star, 22 Sept 1945:

Obviously it's mad. Certainly it's charming, this whole

fantastic tale of Miss Carter and Joe, now a good genei, who in Sulayman's day

was a bad one, and so was locked in a cedar tree as punishment.

…

Miss Carter herself is as English as mutton, getting on—47 to

be exact—doing her daily stint at her war job in the censorship office, wearing

old-but-well-cut tweeds and, in short, living about the loneliest, dullest life

imaginable. And then comes Joe. And from then on it's anybody's ball game.

Nothing is impossible. … Joe is what every woman would like to have around the

house. You'll love him.

…

Not until you've finished the book do you realize how much

you've learned about wartime living in England…

I

also recently came across a rather fascinating profile of Burton/Kerby in the Windsor Star, dating from 22 Jun 1945,

with lots of interesting details contrasting wartime Canada and wartime England:

For one who has been away from Canada 10 years, the funniest

part of returning home lies in finding the cities all still standing up, Miss

Betty Burton, who has been in London, England, since 1935, declared this

morning…

…

"When the ship pulled into Montreal," Betty said

this morning, "it was the strangest thing to see the houses all standing—a

whole city and not a single house or building blown down."

The first thing Betty did, on arriving in Montreal, was to hie

herself to a store where she bought a bottle of mild. What a delight it was

after the condensed milk of the ship and the powdered milk of Britain!

…

Real eating began when our ship left Liverpool. From there out

folks who had been on short rations for years glorified in fine meals at tables

on which there were sugar bowls filled with sugar.

"On the boat," Miss Burton said, "we had meat

twice a day. … In the 11 days across the Atlantic, I gained 12 pounds. Everyone

on the ship gained from seven to 15 pounds."

…

In addition to her regular full-time employment and her

authoring in her spare time, Betty, like all the women in Britain, did her

share of work during the blitz, as a fire-watcher by night—one night in every

six. That night, if you were up all night, you just skipped sleeping and went

back to work at the usual time in the morning without it.

Betty's job, with the fire-watchers, was as a messenger.

"And so," she said, "if my grandchildren ask,

'Gramma, what did you do in the war?' I'll be able to tell them, 'Children, I

ran like the devil.'"

In one raid, Betty was injured. Her job then was to climb out

on a high ledge and scoop up the shattered glass, so that chunks of it wouldn't

fall on the people in the street below. In the course of doing that, she cut a

finger.

…

Betty was fire-watching the night the doodlebugs first came

over London. The doodlebugs and the rockets that came over later were

nerve-wracking weapons, which the British felt were not quite fair.

"It was the inhumanness of the V-weapons that got most

people, I think," Betty said.

I

reviewed the novel here

early this year.

Part way through and enjoying it. Joe is an interesting invention: In attempting to explain culture/war/all sorts of things to Joe, Miss Carter and the author are explaining things to themselves and the reader.

ReplyDeleteJerri

I've been wallowing in your latest publications. Miss Carter and the Ifrit was great fun - a welcome relief from the realism of the others!

ReplyDelete