Last but not least, in my fourth and final post highlighting authors recently added to my main writers list, I have 14 authors whose work was comprised of or included more or less traditional mystery or crime novels. The best news of all is that three of these authors have already been reprinted.

The British Library Crime Classics series has already reprinted the one mystery by BILLIE HOUSTON, Twice Round the Clock (1935), a country house mystery. Along with her sister Reneé, as the Houston Sisters, she was also an actress and dancer.

And Moonstone Press (see here), who are doing some really interesting work these days, have reprinted two more of the authors I've just come across. ZOË JOHNSON was the author of two mystery novels, the first of which is now available again. At the Sign of the Clove and Hoof (1937) (a book I have actually read, no less) deals with murders in a zany English village worthy of early Gladys Mitchell or Edmund Crispin. I found the ending a bit anticlimactic, but otherwise loved it, which means I'm hoping Moonstone will also reprint her second novel, Mourning After (1938), about tensions arising from a wealthy old man's will, which leaves everything to his children unless there's any suspicion of foul play, in which case it goes to a cousin. Said cousin shows up on the scene, of course...

Moonstone has also reprinted all three of D. ERSKINE MUIR's mysteries. Muir was a teacher, historian, biographer, and author of four novels in all. The first (as Dorothy Muir), Summer Friendships (1915), is a non-mystery, epistolary novel in which a group of caravanners venturing from the Scottish borders to Loch Maree all write letters to a young widow relative, "who herself becomes involved in the plot before the happy end is reached." Unsurprisingly, I'm intrigued… Following her husband’s premature death in 1932, Muir returned to fiction to support the family, including three mysteries based on true crimes—In Muffled Night (1933), based on the 1862 murder of a servant, Jessie McPherson, in Glasgow, Five to Five (1934), on the 1909 Glasgow murder of Marion Gilchrist, and In Memory of Charles (1941), on an unidentified case, but one which, Muir assured her readers, happened as described. In addition to fiction, Muir published biographies of Queen Elizabeth, Florence Nightingale, Machiavelli and Cromwell, histories of Milan and Germany, a guide to Oxford, and other works of local history, as well as The Art of Conversation (1953). Lift the Curtain (1955) was subtitled "reminiscences of the author's early life."

So far as I know, those are the only authors in this post who have been reprinted, but a few of these others might have potential for the future. I. R. G. (INNES RUTH GRAY) HART was an artist as well as the author of eight novels which, according to contemporary reviews, often combine mystery, adventure, and humour. Frontier of Fear (1928) takes place in “a broken-down cottage on an island, separated from the coast of Ireland by a narrow but treacherous channel.” The Double Image (1928) is described as “a murder story of an unusual type, which incidentally includes an excellent satire on London suburban life.” Dead Hand (1929) features “a twin sister resolutely carrying out the broken dying wishes of her brother who is killed in an accident. … Miss Hart has subtlety and humour.” Facets (1930) looks at a family’s suspicions of a dead man’s widow. In Forests of the Night (1930), two men go on an expedition to the Malayan jungle, only one returns, and subsequent revelations cause repercussions among their family and friends at home. Adjustments (1931) is a “very entertaining book about a mother who would commit any small crime for the sake of her children and not even recognise any wrong. There is a delicious irony in the gentle exposure of Ruth Lambe’s fraudulent machinations.” In Like Water (1931) a girl who had a fling with a soldier, soon after killed in battle, convinces his mother it was a great love. And Coloured Glass (1933) features the intrigues and tragedy around the young, selfish, unlikely wife of a vicar in a country town. Hart is listed on a 1925 passenger list as a teacher. Predictably, her books are mostly impossible to find in the U.S.

Perhaps along similar lines is EDA KATHLEEN BRIDGMAN, who published as Lee Lindsay and Jean Barre (as well as four early titles as Jean Barr, oddly enough—a switch of publishers seems to have inspired the extra "e"). She published more than 40 novels in all, many romantic comedy adventures, some with definite mystery or thriller elements. A 1936 review refers to “her usual sorcery of brilliant colouring, music, quick and unexpected happenings and humour ‘straight off the ice,’ and lures us into forgetting that there are such things as boredom, stormy weather and lack of money.” Among her Barre titles, The Swiftest Thing in Life (1931) tells of three young London flatmates and their adventures in love, with side tracks to the U.S., Cornwall, and Sicily. A Hunting We Will Go (1934) features a young man in a battle of wits with jewel thieves—a review described it as “not exactly a thriller,” but praised it nonetheless. The King's Pearl (1934) also features jewel thievery, involving an impoverished young gentlewoman and the title jewel, formerly belonging to Charles II. The Desert Son (1935), which is particularly enticing me, is “an arresting tale in which a man who has lived an amazingly lawless life in the desert suddenly bounces into English country life with oddly humorous results.” Gather Ye Rosebuds (1937) is “the story of little Tara Mallison, who blossoms from being her aunt’s unofficial lady’s-maid to mistress of a mansion. Interwoven with the main theme are the love affairs of two charming characters—Rosita and Roselle Vesant, known as the ‘Rosebuds’ of New York.” The Lee Lindsay titles, also romantic and adventurous in tone, perhaps have a bit more melodrama thrown in. The Three Buccaneers (1934) features a heroine abducted by an unrequited lover. In The Moon Through Trees (1935), a young Chelsea model is on a quest to find her father and sister. Unarmoured Knight (1936) features a stolen Buddha with a curse attached. And Dress Rehearsal (1937) features a love triangle playing out in a theatre. I have a copy of The Adventures of a Lady (1944), with a dustjacket no less, but haven't got to it yet.

I also have one of DORIAN LEE's non-crime novels waiting to be read. She wrote over a dozen in all, and Hubin lists her in his Crime Fiction database, but of the details I’ve found, only two of her novels definitely seem to fit: Strange Partner (1948) is certainly in the mystery/thriller line, with a young couple’s plane forced to land in the South Seas and drama involving the wife’s former beau to follow, and Cut the Cards, Lady (1952) is about a fortune teller who sees murder in the future. Snakes Have Fangs (1946), about a young woman shipwrecked on a surprisingly luxurious South Seas island and threatened by the natives could have thriller elements, as could Dark Star Rising (1947), about supernatural dabbling that threatens a soon-to-be-married couple. Lee’s more light-hearted work seems to include The Fledgeling (1952), in which an adopted girl “is used to a gay life and causes havoc in the Rideouts’ placid world … It would be difficult to resist her infectious gaiety and charm,” while Green Bracken (1953) is a “charming and light-hearted romance set against the nostalgic background of a caravan holiday by the sea” and Wild Apple Orchard (1954) is “the happy, heart-warming story of the Dennistouns and the old orchard they hopefully converted into a caravan camp.” Others about which I’ve found information are Uncertain Treasure (1947), in which a young woman is mistaken for a film star, Lover Come Home (1950), about a “temple dancer of the East” dealing with the snobbery of an English village, and Luke's Summer (1951) about a “surplus woman” who marries, at 37, a widowed doctor with teenage children. In The Captive Years (1951), a divorced couple struggles to establish new lives for themselves, while Prisoner Go Free (1954) features a woman struggling to adapt to life after being released from prison, and Home to Our Valley (1956) is about a young Austrian woman returning home to conflict and heartbreak following an extended stay in England. I could locate no details about her three remaining novels—Crooked Paths (1943), Sandover Goes Gay (1946), and The Bad Companions (1955).

Somehow, I already had half of the two-woman team comprising the pseudonym Hearnden Balfour on my list—I added Evelyn Balfour a while back, but neglected to add BERYL HEARNDEN. She was a progressive farmer, journalist, editor, and author of three mystery novels with Balfour. These are The Paper Chase (1927, aka A Gentleman from Texas), about an ex-officer who answers an ad and gets pulled into adventure and drama, The Enterprising Burglar (1928), about "a burglar, who robs from the rich and distributes to the poor, [and] escapes from a train wreck with the brief case of a dangerous enemy agent," and Anything Might Happen (1931, aka Murder and the Red-Haired Girl), about intrigue issuing from a reformed criminal and his double. All featured series character Inspectore Jack Strickland. She later collaborated with Louise Howard on What Country Women Use (1939), a guide for rural women.

Only one of IRIS WEDGWOOD's four novels belongs in this post, and that perhaps only peripherally. The Livelong Day (1925) is a tale of the murder of a drunken Earl and the difficulties his widow has until her new romantic interest can be cleared of the crime. But it's apparently not a mystery per se, as the identity of the murderer seems to be widely known; rather it's a look at the trouble caused by suspicion. The Iron Age (1927) seems to have to do with a woman trying to save her son from a career as an ironmonger. Perilous Seas (1928) has Ruritanian elements, stemming from a young wife's adventures making nice with the king of a Balkan State in order to further her husband's career, only to have said king fall in love with her—just on the eve of a revolution. And The Fairway (1929) deals with the fortunes of several men and woman in the industrial North of England. Wedgwood's mother, rather better known these days than she herself, was historian C. V. (Cicely Veronica) Wedgwood. Later, Iris published two non-fiction works, Northumberland & Durham (1932) and Fenland Rivers (1936). Joseph Conrad’s story collection Within the Tides (1915) was dedicated to Wedgwood and her husband Ralph, who was knighted for his work as a railway administrator.

A couple of "one hit wonders" seem, from the information I've found about them, to have potential. AGNESE AUTUMN was the unidentified author of one novel, The Gold and Copper Delamonds (1930), an “interesting and ingeniously invented” mystery with supernatural elements, about murder at a fancy dress ball—possibly committed or inspired by a portrait which vanishes thereafter. Hubin concluded the name is a pseudonym, but I’ve made it no further.

And I'm somewhat intrigued, too, by BRIGID MAXWELL's single mystery, The Case of the Six Mistresses (1955), about a newspaper special correspondent who has kept a busy social life. A critic noted that Maxwell “develops her story with a swing and has a long list of pleasant characters." Maxwell was born in Australia, but appears to have emigrated as a small child. She was a journalist, translated a biography of Mussolini from Italian, and wrote several short pamphlets for local agencies, including a brief history of Hampstead.

I also wouldn't turn down an opportunity to read Breakfast for Three (1930), a mystery set on fictional Redmoor, in which a wanderer comes across a cottage with a corpse inside, was praised for its local color. That book was co-written by Marguerite Bryant, already on my list, and GERTRUDE HELLEN MACANALLY. The two also published one earlier novel, The Chronicles of a Great Prince (1925), a Ruritanian adventure set in 1817.

Another unidentified author, ELSA GLEN published a single thriller, The Secret of Villa Vanesta (1935), a “Rivieran murder tale of a neurotic girl, a somewhat unsympathetic English painter, and two modern English women,” also described as "a tale of suffering, occult influences, and weird happenings." Hubin concluded her name, too, is a pseudonym, but there are too few leads to pursue.

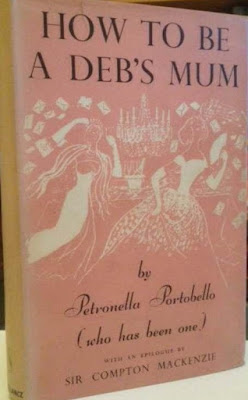

I couldn't locate covers of any of Hartley's fiction,

but this cookbook cover caught my eye

Suffragist, journalist, and cookbook writer, OLGA HARTLEY also published three novels. Anne (1920) involves an orphan who marries one her guardians, miserably, her child dies, and she finally runs off with her other guardian (after he’s unjustly served five years in prison)—but despite this subject matter, it was repeatedly noted by reviewers that it was humorous—“A comedy with just that touch of sadness that brings laughter close to tears.” The Malaret Mystery (1925) and The Witch of Chelsea (1930) are mysteries—the former set in Morocco, the latter featuring the murder of a former PM and a Cockney detective. She also wrote or co-wrote several cookbooks, including with Hilda Leyel (1880-1957, aka Mrs. C. F. Leyel). A 1923 libel case was brought against Hartley, involved the attempted sale, by Hartley and her mother, of "Golden Ballot" tickets to plaintiff; she lost, but the damages were one farthing and the judge dismissed the action as frivolous.

And finally, VICTORIA YORKE published three novels. Five of Hearts (1927) tells of two sisters, alone and penniless, and how they prevail—"Love and business mix well in this novel, which has much to commend it, for it is well and smartly written and is off the beaten track of fiction." Her other two have crime elements—Sealed Lips (1928), in which an actress kills her blackmailer and goes on the run, and Suppressed Evidence (1931) about a man who commits perjury to save his wife from suspicion, and the repercussions of his lies. She could well be the Victoria Margaret Yorke (née Gerald) 1900-1976, but there’s too little to go on to be sure.

And that's that for now. It's given me several new authors to search for, and no doubt there are many more to be found in the same fog of obscurity from whence these came.

%20-%20Adventures%20of%20a%20Lady%20fc.jpg)

.JPG)

%20-%20Jezebel%20and%20the%20Dayspring.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)