I've

been meaning to write about this novel and about Clavering herself for some

time. She is certainly a

"lesser-known" writer by any definition, and her books, with the exception

of the present one, are virtually nonexistent outside of the major U.K.

libraries.

Fellow

blogger Jeanne at A Bluestocking

Knits recently provided me with a plethora of information about Clavering,

provided to her a while back by a cousin of Clavering herself. Jeanne had been meaning to write more about

her, but hadn't gotten to it, so she graciously shared the information with me

and is allowing me to share it here.

I'm

planning to write a more in-depth post on Clavering herself in the next few

days, but thought I'd start off by discussing the one novel of hers that can be

tracked down with relative ease—especially since it happens to be quite

relevant to D. E. Stevenson fans as well.

Be sure to check out Jeanne's original post

on this novel, too, which is what led to her contact with Clavering's

cousin.

I first

read Mrs. Lorimer's Family (published

in the U.K. as Mrs. Lorimer's Quiet

Summer) a couple of years ago, after it was recommended on the D. E.

Stevenson discussion list as a DES-ish book with more than the usual number of

DES connections. Molly Clavering was a

neighbor of Stevenson's in Moffat, Scotland (called Threipford here), and the

novel is at least somewhat

autobiographical. The main character,

Lucy Lorimer, is obviously modeled on Stevenson, and her close friend Grace

("Gray") Douglas is based on Clavering herself, who had already

written several novels, albeit with considerably less success than Stevenson:

The two were friends and had been for many years before Miss

Douglas, a little battered by war experiences, had settled down in Threipford,

to Mrs. Lorimer's quiet content. Not only were they genuinely fond of one

another, but they had many mutual interests; but neither had ever tried to

probe into her friend's innermost reserves, and this reticence seemed only to

have strengthened the friendship. Both wrote; each admired the other's work.

Lucy possessed what Gray knew she herself would never have, a quality which for

want of a better name she called "saleability." Lucy had made a name

by a succession of quiet workmanlike novels, redeemed from any suggestion of

the commonplace by their agreeably astringent humor and lack of sentimentality.

Now she earned a comfortable income, and if she did not actually supply the

family bread and butter, the family jam and cake depended largely on her.

In an

article Clavering wrote about her friendship with Stevenson—in which she

described her as "a quiet woman with curls of silvery hair, blue eyes and

a low-pitched unforgettable voice, wearing for choice good tweeds and well-cut

plain shoes"—she also noted how offhand Stevenson was about her writing:

Writing of course is her chief interest, but she does not

allow it to absorb her entirely, except when a new book is under way, and even

then she will emerge, dazed and blinking a little, to answer the calls made on

her by her family and friends. Asked in respectful tones if she has been

WRITING, she is quite likely to answer, "I've been making a cake," or

"I've been helping John to cut down a tree in the garden."

That

the tone of Clavering's short memoir matches so well the novel's descriptions

of Mrs. Lorimer suggests that the novel is intended to be a fairly accurate

portrayal of Stevenson.

Since

I haven't been able to track down any of Clavering's other novels, I can't say

for certain, but it seems too that Clavering might have been emulating

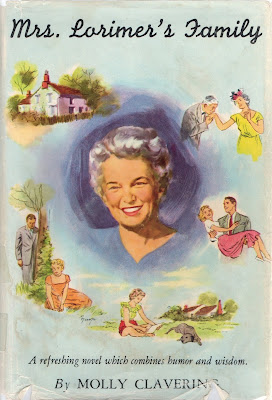

Stevenson here in hopes of achieving comparable commercial success. Mrs.

Lorimer's Family is very much in the DES style—a pleasant, cozy sort of

novel about Lucy, her husband, her four children, three of whom are married,

and several grandchildren, who have all come home for a visit. In addition, Gray is often present to provide

moral support. If it was an attempt to

reach a broader audience, the attempt may have been successful, as this seems

to be the only one of Clavering's novels to have been published in the U.S.,

and it was taken up by the People's Book Club (with its usual colorful and

interesting endpapers).

|

| The endpapers are always a high point of a People's Book Club title |

The

novel is gently humorous, and the problems faced are generally minor and easily

resolved by Lucy's and/or Gray's wisdom and life experience, but I found it to

be completely entertaining and enjoyable, even during my recent second reading. Reportedly, Stevenson's children

were somewhat upset by Clavering's portrayal of the family, and it's easy to guess

why this might be. While Stevenson

herself gets off lightly in Clavering's obviously admiring portrayal of Mrs.

Lorimer, the children are a bit more problematic. (Presumably, however, any resentment was not lasting, as Stevenson's granddaughter wrote an affectionate obituary for Clavering in the local paper.) Daughter

Phillis, for example, who feels neglected by her husband, is presented as rather

temperamental and a bit spoiled, and Lucy vehemently disapproves of son Guy's romantic

interest in a neighbor girl.

Most

entertaining, though too brief, is the portrayal of daughter-in-law Mary, who,

having flown planes during the war, now finds herself unequal to the challenges

of housekeeping. Clavering doesn't make

as much as she could of this rather poignant situation—one undoubtedly repeated

many times in the lives of women all across Britain in the years after their

war work had ended and they attempted to return to domesticity. But be that as it may, the solution Lucy

suggests to Mary seems so perfectly Stevenson-esque that one feels it must be a

glimpse of the real personality behind Clavering's portrayal:

"Instead of being apologetic about your absent-mindedness

you must turn it into an asset," said Mrs. Lorimer impressively. "You

must be an eccentric, that's all. It will work beautifully. Eccentrics always

seem to be well served. Thomas must explain to the new cook that you were flying

all through the war, and that you are not to be bothered with household

affairs. The explanation will come better from him—"

"I am to have a mind above housekeeping, in fact?"

"Well, you do seem to, don't you, Mary dear? I mean, your

head is always up in the sky," said her mother-in-law, but very kindly. "If

your new cook really is a good one, she will be pleased to have the

responsibility. Once she understands that you are something out of the

ordinary, she will run the house for you, do the ordering of the food and cook

it, so you and Thomas ought to be quite comfortable and well fed. It isn't as

if you can't afford to pay a staff, after all."

And

when Mrs. Lorimer goes on to add some detail about her own cook, a Stevenson

fan could hardly fail to imagine Miss Buncle and her beloved Dorcas:

"I never waste my time and efforts on useless

endeavor," said Mrs. Lorimer. "And I do understand, because when I am

writing Nan takes over the housekeeping for me. She thinks I am a little mad at

those times, but she is rather proud of me. I don't see why your cook shouldn't

be the same."

It's

difficult, too, not to be charmed by Clavering's self-portrait in the character

of Gray:

Thimblefield, an old cottage, had been built on to at

different times; one owner had added a room, another had put in a dormer window,

and the result, though highly irregular, was attractive and harmonious. Miss

Douglas loved her funny little house and was happy in it, and knew that she was

happy, an enviable state which is rarer than one would suppose. She had reached

that half-way stage in life when there seems to be a pause before starting down

the far side of the hill to that unknown valley where death is waiting, and the

dark river that has to be crossed. Youth with its fevers and unrest, its

terrible miseries and lovely ecstasy, was behind her, gone for ever. She knew

it was a loss, but an unavoidable one, and very sensibly seldom looked back

over her shoulder.

Although

Clavering herself, like Gray, never married, it's nice to see from passages

like this one that her life may not have been lacking in romance. And her policy of not looking back may be

reinforced by one of the most DES-ish events in the novel—Lucy's encounter with

an old beau at a party:

Determinedly she drew the others into the conversation, but it

was difficult, with Richard now muttering into her ear how wonderful it was of

her to remember that he appreciated good cooking. Mrs. Lorimer could not

imagine how some women seemed to find it romantic and exciting, even when they

were happily married, to meet an old flame again. She was finding this

maddeningly tedious, and it seemed impossible to make Richard understand that,

far from being an old flame, he was the deadest of dead ash to her.

I

admit that when the "old beau" was first mentioned, I perked up,

shamelessly hopeful of some gossip. I

have always been intrigued by the character of Tony Morley in Stevenson's

loosely autobiographical, humorous Mrs.

Tim novels. Morley shows up in all

of the Mrs. Tim books, and always he persistently flirts with Stevenson's

alter-ego, Hester. Always, too, Hester

is either oblivious to his attempts or willfully misinterprets them (either

interpretation makes for an entertaining way of reading the scenes in which

Morley appears).

There's

certainly never any indication that Morley is an "old beau" of

Hester's, but I wondered nevertheless if, just maybe, Clavering had

based the old beau in this novel on a real figure in Stevenson's life. It's not such

a stretch, if we take both the Mrs. Tim novels

and this one as based on Stevenson's real life.

But alas, there was no revelation here that I could find. The old beau in Mrs. Lorimer's Family is truly an old bore, who bears no

resemblance to the charming Morley.

But one

more glimpse of Stevenson does seem to come through when the old bore mentions

Lucy's literary success:

Mrs. Lorimer was conscious that she was babbling with most

unusual loquacity, and it did not make her any happier to have Richard

murmuring in his annoyingly confidential manner: "I read an article about

you in a magazine, Lucy, by someone who described you as a very quiet woman. I

must say I shouldn't have recognized you—"

"Oh, you can't go by those interviews with reporters. I was

probably struck dumb and couldn't think of anything to say on that

occasion," answered Mrs. Lorimer, unable to stem the nervous rush of words

which was afflicting her.

These

"insider" glimpses of Stevenson and her family are certainly fun (and

if you'd like to know more about Stevenson, be sure to check out two

wonderfully informative DES sites here

and here),

but there are other memorable moments in Clavering's novel as well—enough to

make me yearn to get my hands on more of her books. As several folks at the DES discussion list

suggested, she might be a perfect choice for a Greyladies author. It's true enough that she lacks some of Stevenson's

subtlety in developing characters, and she is not always willing to trust her

readers to find the humor of a situation, so that jokes are sometimes painstakingly

spelled out. But it would be quite interesting

to see what Clavering was able to do when she was not writing about a close friend—and not, perhaps, emulating her

style.

More to

come on Clavering in the next few days, with other biographical information as

well as information about her other writings.

For now, suffice it to say that she was considerably more prolific than

I had ever realized…

Of course, as a Dessie, I had to buy this and read it, and it sits on my Stevenson shelf as an honoured guest, but I never really warmed to it, though I tried. I really did. Perhaps another reading, someday?

ReplyDeleteI understand, Susan. This novel definitely doesn't have all the charm of a really good DES. But it really made me want to see what else Clavering was capable of. However, apparently an expedition to the British Library or the National Library of Scotland would be necessary in order to read her other books--which I certainly wouldn't mind, if only it wasn't for pesky details like money!

Delete