In retirement Uncle John went on a cruise round the world, met a lady on board ship and fell in love with her. His wife wouldn't divorce him so they lived in sin. Fortunately, by this time Big Granny and Grandfather were dead, but family eyebrows were raised. Mudzin, who disapproved violently of any sort of unofficial liaison, was a bit nonplussed, but her loved brother could do no wrong and the Lady Friend was accepted. As a femme fatale she was a disappointment, being well-born and cultured and wearing Heath hats and tweeds. They settled down in a nice house at Ashtead, delighted to be excluded from society, and spent their time gardening.

Most of you know (and, presumably, love) Joyce Dennys as the author of two collections of fictionalized letters from the World War II Home Front, Henrietta's War and Henrietta Sees It Through. Although not compiled into books until 1985 and 1986 respectively, the letters—purportedly to a good friend in the military—were written and first appeared in Sketch magazine during the war years, and provide, with delightful humor and accompanied by Dennys' incomparable illustrations, an unforgettable variation on the usual WWII diaries and memoirs. An even funnier Provincial Lady in Wartime, I might say (courting controversy). Which reminds me it's high time for a re-read of both…

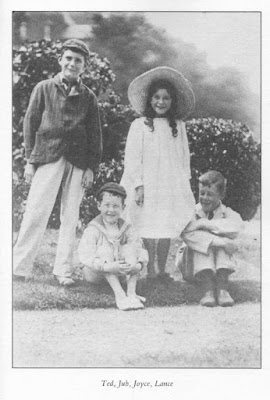

But two years before Henrietta's War appeared, Dennys published And Then There Was One, a short memoir, by turns funny and poignant, of her childhood. Short indeed, weighing in at less than 100 pages, even including a fair number of photos and illustrations. It's a shame that it's not a whole lot longer, but even so it has all the charm one would expect from Dennys.

It also sheds an interesting and sometimes sad light on the families of men who made their careers in India. In some ways Joyce was lucky, since after her harrowing birth in India, during which her mother nearly died, her mother brought Joyce and her three older siblings back to England to live, and remained with them there for several years after her husband's return abroad. In many families, of course, both parents would abscond to India leaving their offspring with relatives or friends or in boarding-school. Indeed, as Joyce describes, the family home provided shelter for many of these orphans of empire:

The house was convenient for her own children and for various nephews who were dumped at Number Five when their parents returned to India, and removed again when the precious furlough came round, only to be dumped once more for tearful farewells when it was time to go back. Not that the nephews minded, for they looked upon Number Five as their home.

Joyce Dennys as a young woman

Difficult for us to imagine today, and as time went on India also stole away Joyce's beloved brothers, which must have been difficult, however matter-of-factly she was able to reflect on it late in life:

Children are bad letter-writers, and when Guy went to India he went out of my life, and I transferred my hero-worship to Lance. Then he too disappeared to India, and though we occasionally wrote to each other, he gradually faded from my memory. These sad family amputations were accepted without comment at Number Five.

The book goes on into amusing and charmingly eccentric descriptions of Joyce's youth and schooling, her first discovery of art in drawing classes "presided over by the form mistress who knew as much about drawing as a piece of india-rubber", and the trials of her teachers, including a choice tidbit which ends with this:

At one time Miss Graham disappeared for several weeks and it was rumoured she was having a nervous breakdown. If this was true I was largely to blame, but even then I felt no remorse.

Rather poignantly, as we hear of Joyce's own discovery of art, we also gather that her mother had frustrated aspirations in art. Joyce recalls the ruthless selfishness of childhood in relation to her mother's dreams:

At one time she went to some art classes given by a Mr Vicarji. They were her only indulgence and she loved them, though Nan disapproved of her having any interests outside the house. After a time she stopped going to the classes. I don't know why but I expect it was because there wasn't enough money to pay for them. None of us enquired and nobody sympathized.

It's no comfort to know what good company Mrs. Dennys would have been in at that time—how many other women could not develop their talents and potential.

I could end up quoting the entire memoir, but it will suffice to say that it's a lovely read, and Joyce's sometimes unusual perspective on things are fascinating in relation to the culture of the time as well as to her later life and talent. It's out of print at this point, but copies are fairly readily available second-hand. Who knows, someone may also reprint it someday!

I was lucky enough to pick up a signed copy of this years ago. I'd already read and loved the Henrietta books (and have reread often since) so I was thrilled. I can also recommend it. I love her illustrations, which I think she did for all her own books. More pics here

ReplyDeleteOh, lovely to have a signed copy! I only wish she had written more--how wonderful if we had Henrietta's diaries from the postwar period and from the 1960s as well. If only!

DeleteThere's another, similar Joyce and her brothers. Look up Three Brothers by Joyce Grenfell: https://www.monologues.co.uk/First_Ladies/Three_Brothers.htm

ReplyDeleteSimilar indeed! Thanks for sharing that. I've always meant to read more of Grenfell as well.

DeleteI marvel at how you unearth information about these lesser-known writers, but I really appreciate your work in doing so. I love Joyce Dennys’ Henrietta books and was glad to learn more about her.

ReplyDeleteThanks for you kind comment. I am an obsessive digger! And certainly more to come about Joyce, as I seem to be on a roll with her...

DeleteThis sounds delightful, Scott.

ReplyDeleteBut the title sounds ominous. Do the others all die off, or does it refer to them all leaving home?

Joyce was my great grandmother, I spent a good amount of time around her in my childhood and up until today I didn't even know this book existed.

ReplyDelete