Perhaps it was the Marc, or the cherries flambées, or both, or merely a selfish desire to hear my own voice, which urged me to try to explain: suddenly I wanted to share my bewildering realisation that no one is set in a mould, that each of us is capable of behaving wildly, temporarily out of character: that occasionally the limiting constrictions move away. All the reasons why this or that cannot be considered are no longer present, or no longer relevant. The railings, the boned corsets of the mind which keep the body in check may be replaced tomorrow, or the day after, but just now and again, miraculously, the strings are slack.

The trouble for Marianne, the narrator of Kathleen Farrell's rather brilliant fourth novel (of five), is that the boned corsets seem to snap back into place too quickly for her wild behavior to have a lasting impact. Marianne is in her late thirties and has seemingly led a rather ordinary, uneventful life. When the novel opens, she is in an attic room in a Paris hotel, wondering if she has missed her chance.

We then flash back to a few weeks before. Marianne is traveling in Switzerland as companion to Lucy and Arnold, an older pair of siblings who might be her aunt and uncle (she says she was told to call them that as a child, but the relationship is never made explicit). No other relatives seem to be mentioned, which may explain the sense of isolation around these characters.

Lucy and Arnold have spent their lives together, in what can only be called a codependent relationship, snarking and nagging at one another, each complaining that the other has stunted their life but simultaneously relying on and enabling each other. We only learn the truth of their situation (if truth it is) late in the novel, though a careful reader is likely to guess some of it well before Marianne learns of it, but their secrets, such as they are, aren't really the point of the novel. It's more the way that their suppressions and damage, the ways that they have limited their lives, cause Marianne to reflect on her own and the decisions she makes in the novel, as she engages in a mild fling with a distinctly unglamorous Swiss tour guide.

It's really very much as if a Jean Rhys character, in rather less disrepair than usual, has ventured into an Anita Brookner novel, haunted by shades of biting Barbara Pym wit. And despite the fact that very little happens except a lot of conversation and some melancholy mulling of the past and present, I was more or less engrossed throughout. Farrell's prose is elegant and funny even as it makes clear that the characters and situations are not elegant at all, at times even sordid.There are some breathtaking (if sometimes harsh) insights into life and the way folks live it, including the quotation at the beginning of this post and this doozy spoken by Lucy, which made me stop and ponder a bit:

'When I said that Arnold "stopped" my marriage, it was not quite in the way you think. Apart from that it is all very well,' she said, 'to make other people an excuse for what one has not done, but that is seldom true. We are all selfish, if one considers precisely—although I know I am contradicting myself—and if we are certain of what we want we shall try to get it, no matter who stands in the way.'

There are some wonderful exchanges, particularly between Marianne and Lucy, and even when they're about the most trivial things, they're often laced with deeper implications, as in their discussion of Marianne's unaccountable liking for "Marc" (always capitalized here, but according to Google, which explains that it is much like grappa, generally written "marc"):

She took such a small sip of the liquid that there was none for her to swallow. 'It's so bitter and hot,' she said. 'Where did you learn to like such stuff?'

I reminded her that at my age one does not remember learning; that I had lived years enough to happen to acquire a taste for many things—and Marc was one of them.

'It has never happened to me'—Lucy wiped her mouth with a scrap of handkerchief—'and I must say that I am glad it has not, and I can't see how it could. And when I think how you were brought up, it seems so ... so out-of-the-way.'

But that was a long time ago.

'Surely those are the formative years? When one is a child, I mean—and then at school—and the convent you used to attend—no, it does not fit.'

Fortunately, or unfortunately, one seldom knows which, those were not the formative years for me.

Which reminds me, readers who are particularly hung up about quotation marks might be annoyed by Farrell's use of them for other characters but not for her narrator. I found it interesting, though, because it forces the reader at times to question whether the words are spoken or only thought, which in turn forces the reader deeper inside Marianne's consciousness. On the other hand, who can say what is portrayed accurately here, in view of this crème de la crème sample of Marianne's quotable moments:

No doubt I said something, but what I cannot recall. All these conversations are more or less what was said, although much I have forgotten, and more misinterpreted, perhaps.

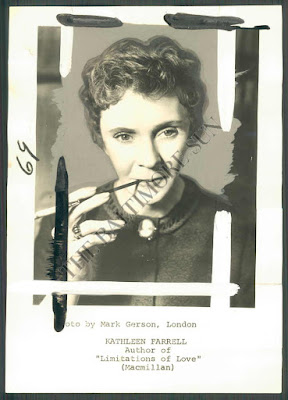

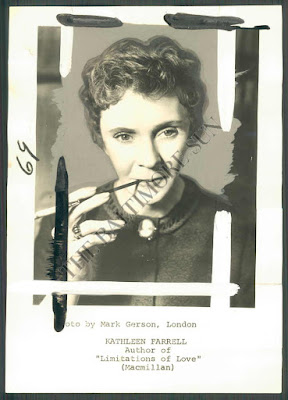

I first read, and wrote about, Kathleen Farrell so much longer ago than I thought—back in 2013 not long after starting this blog (see here). I reviewed her third novel, The Cost of Living (1956), and enjoyed it quite a lot (and I see I compared her to Barbara Pym there too!), so it's shocking I've only now followed up with reading another of her novels. I'll have to make time for another one a little sooner this time!

As an aside, Farrell's "longtime companion", Kay Dick, has seen a bit of a revival this year, with the reprinting of her 1977 novel They by Faber in February. Perhaps the same sort of revival will soon follow for Farrell?

%20-%20Barbara%20Goes%20to%20Oxford%20pc.jpg)