I'm always thrilled to receive my physical copies of the Furrowed Middlebrow titles from Dean Street Press, and even though I've already seen the covers and the intros and (obviously) read the books long before they're released, opening the box with the actual books always feels a bit like Christmas. It never gets old, and I always have to pinch myself a bit to believe that they're really "my" books.

So now that I've previewed all the titles over the past couple of weeks, here's a glimpse of the full set of new, World War II-themed titles. And here also is a thank you for all the wonderful support the books have been getting from readers and bloggers and reviewers, and all those reading the books and recommending them to friends and relatives and, indeed, total strangers through the magic of the internet!

Before too long, we'll have an announcement of another set of Furrowed Middlebrow titles (three authors, eight titles), tentatively set for January release. I think you'll be pleased... In the meantime, I might be posting a bit less for a time, while I push ahead more intensely with a major update to my author list, including nearly 150 new authors (some of whom I've already sampled, with varying results), and revised, expanded, and/or corrected details for hundreds of the 2,000 authors already on the list. That's my main mission for the next couple of months, and then we have a holiday to Philadelphia, Boston, and Vermont coming up in October, so I have plenty on my plate!

Meanwhile, enjoy the new books (and the older ones!) and look forward to more coming soon.

off the beaten page: lesser-known British, Irish, & American women writers 1910-1960

Wednesday, August 21, 2019

Saturday, August 17, 2019

Sneak preview, FM38: BARBARA BEAUCHAMP, Wine of Honour (1946)

From

Elizabeth Crawford's informative introduction to Wine of Honour:

Barbara Proctor Beauchamp (1909-1974) was born in Surrey, the

eldest child of a stockbroker, and brought up and educated in France and

Switzerland, where her parents had a chalet at Château d’Oex. Her younger

brother and sister, twins, died young; Alice aged 21 in 1934 and Philip killed

in Singapore in 1942.

Among

other things, the family chateau in Switzerland explains the use of that

country as a setting in at least two of Beauchamp's novels, Without Comment (1939) and Ride the Wind (1947). Reviews of

Beauchamp's books are difficult to come by—she is one of those authors who seem

to have been largely ignored by critics—but she apparently had something of a

fan in well-known critic (and novelist) Frank Swinnerton, whose review of the

former novel in the Observer notes,

along with some nice praise, that it has autobiographical elements:

Now, the truest-seeming book I have read this week is

"Without Comment," which not literally but in its type suggests first

hand experience … Miss Beauchamp tells in "Without Comment" the brief

tale of an English family, resident in Switzerland, which is broken by the

divorce of the parents; and she concerns herself chiefly with the doings of two

young girls, one of whom married for love and escape, while the other, through

whose eyes most of the events are seen, allows herself to be seduced in the

modern manner by a handsome flirt and has to wait long for any kind of liberty.

The book is full of crisp observation and outspoken natural talk; its

impressions of the Swiss scene and the Belgian resort in which the children

visit their divorced father are excellent; and while the more poignant

inventions lack force the squabbles, the lighter adventures, and the relations

of the sisters are all excellent. I do not remember better sketches of

neglected, sophisticated girlhood.

If

it's true that the novel was autobiographical, there might be some additional

clues there about Beauchamp's family situation (would that the novel were

available anywhere).

The Daily Sketch felt, by the way,

that Without Comment was

"brilliantly told". Sadly, I've not come across any contemporary

reviews of Wine of Honour at all,

though a subsequent novel, Virtue in the

Sun (1949), was praised by John Betjeman as a "first-class

novel", while Howard Spring (if I'm correctly making out the words of a

badly scanned blurb) said it was "one of the finest presentations of a

boy's mind in such stressful circumstances that I have come on for a long time."

As

you will all know by now from my previous raving about it, Wine of Honour is, among other things, a brilliant documentation of

women, many of whom have been in the services, adjusting to the first few

months of postwar life. Sadly, Beauchamp doesn't seem to have written about the

war itself in her fiction, so it was intriguing to get just one little snapshot

of Beauchamp in wartime from a short blurb in the Montana Standard in 1940 (presumably it was syndicated to other

newspapers as well):

In protest at the "fantastic position" of women

auxiliary firemen in London, two women novelists, Miss Barbara Beauchamp [sic],

have resigned from the force, their chief complaint being that they volunteered

as drivers, but were asked to scrub floors.

The

other woman novelist may well have been Norah C. James, but thanks to a

careless typist or typesetter we may never know for sure. Based on the information from the author bio above, from the dustjacket of The Girl in the Fog, she must have gone more or less directly into the ATS after resigning from the fire service.

Returning to

Elizabeth Crawford's introduction, we do get a glimpse of Beauchamp's postwar

life:

While writing Wine of

Honour Barbara Beauchamp was living not in a bucolic English village but at

9 Cumberland Gardens, Islington, a quiet enclave close to King’s Cross, in the

house she shared with her partner, Norah James, to whom the novel is dedicated.

Norah was also a novelist, notorious as the author of Sleeveless Errand which, when published in 1929, had been censored

on the grounds of obscenity. In this post-Second World War period Norah’s

publisher was MacDonald & Co, suggesting it was not a coincidence that the

same firm published Wine of Honour.

The two women wrote at least one short play together, broadcast on the BBC Home

Service in 1947, and one book, Greenfingers and the Gourmet, which

combined instructions for growing a wide range of vegetables with a 'number of

specially good recipes in which these vegetables played an important part'.

They had been partners since at least 1939 when Norah dedicated her

autobiography, I Lived in a Democracy,

to Barbara, but by the early 1960s appear to have separated and for the remainder

of her life Barbara shared a home with Dr Millicent Dewar, a renowned

psychoanalyst. Barbara continued her journalism career after the war, for a

time reviewing novels for provincial newspapers and herself publishing three

further novels, the last in 1958.

Thursday, August 15, 2019

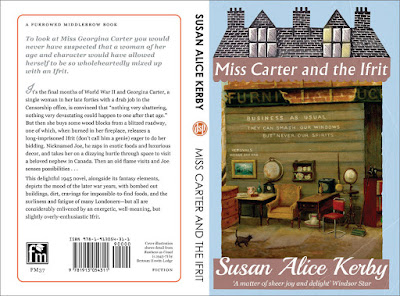

Sneak preview, FM37: SUSAN ALICE KERBY, Miss Carter and the Ifrit (1945)

From

Elizabeth Crawford's excellent introduction to our reprint edition:

Susan Alice Kerby was

the pen name of [Alice] Elizabeth Burton (1908-1990), who had been born in

Cairo, the daughter of Richard Burton (c.1879-c.1908). He was probably English,

while his wife Alice (1884-1962 née Kerby) was Canadian. The couple had married

in Chicago in 1907. It is to be presumed that Richard Burton died around the

time of Elizabeth’s birth because after returning from Egypt to her home town,

Windsor, Ontario, Alice was described as Burton’s widow when she remarried in

October 1909.

We first catch a glimpse of Elizabeth Burton in 1926 when,

described as a student, she sailed, unaccompanied, from Naples to the USA after

spending time in Rome, where she had stayed with an aunt and studied music and

history. In 1929, still a student, she again paid a visit to Europe, perhaps

visiting English relatives. Back in

Canada she launched her career as a journalist and over the next few years

worked in radio and in advertising. In 1935 she again spent some time in

England, arriving back in Canada in June and then in November, in Windsor,

married John Aitken, a fellow journalist. However, the marriage seems to have

been short lived; Elizabeth later recorded that in 1936 she decided to move to

England. At some point there was a divorce and in 1950 Elizabeth changed her

name by deed poll from ‘Aitken’ back to ‘Burton’. However, she maintained her

link with Canada, acting as the London correspondent of the Windsor Star from 1945-1965.

…

Elizabeth Burton’s first novel, Cling to Her, Waiting, written under her own name, was published in

the autumn of 1939 and her second, A

Fortnight at Frascati, for which she used the ‘Susan Alice Kerby’ pen name,

appeared in 1940. There was then a five-year gap until the publication of Miss Carter and the Ifrit in 1945,

suggesting that in the interim she was engaged on wartime business with little

time to write novels. Miss Carter worked ‘in Censorship’ but there is no

evidence to tell us how Elizabeth Burton was employed, although it was possibly

in some similar capacity.

Thanks

to Elizabeth, as always, for unearthing such wonderful tidbits for her intros.

Some choice snippets from

a review of Miss Carter and the Ifrit

in the Windsor Star, 22 Sept 1945:

Obviously it's mad. Certainly it's charming, this whole

fantastic tale of Miss Carter and Joe, now a good genei, who in Sulayman's day

was a bad one, and so was locked in a cedar tree as punishment.

…

Miss Carter herself is as English as mutton, getting on—47 to

be exact—doing her daily stint at her war job in the censorship office, wearing

old-but-well-cut tweeds and, in short, living about the loneliest, dullest life

imaginable. And then comes Joe. And from then on it's anybody's ball game.

Nothing is impossible. … Joe is what every woman would like to have around the

house. You'll love him.

…

Not until you've finished the book do you realize how much

you've learned about wartime living in England…

I

also recently came across a rather fascinating profile of Burton/Kerby in the Windsor Star, dating from 22 Jun 1945,

with lots of interesting details contrasting wartime Canada and wartime England:

For one who has been away from Canada 10 years, the funniest

part of returning home lies in finding the cities all still standing up, Miss

Betty Burton, who has been in London, England, since 1935, declared this

morning…

…

"When the ship pulled into Montreal," Betty said

this morning, "it was the strangest thing to see the houses all standing—a

whole city and not a single house or building blown down."

The first thing Betty did, on arriving in Montreal, was to hie

herself to a store where she bought a bottle of mild. What a delight it was

after the condensed milk of the ship and the powdered milk of Britain!

…

Real eating began when our ship left Liverpool. From there out

folks who had been on short rations for years glorified in fine meals at tables

on which there were sugar bowls filled with sugar.

"On the boat," Miss Burton said, "we had meat

twice a day. … In the 11 days across the Atlantic, I gained 12 pounds. Everyone

on the ship gained from seven to 15 pounds."

…

In addition to her regular full-time employment and her

authoring in her spare time, Betty, like all the women in Britain, did her

share of work during the blitz, as a fire-watcher by night—one night in every

six. That night, if you were up all night, you just skipped sleeping and went

back to work at the usual time in the morning without it.

Betty's job, with the fire-watchers, was as a messenger.

"And so," she said, "if my grandchildren ask,

'Gramma, what did you do in the war?' I'll be able to tell them, 'Children, I

ran like the devil.'"

In one raid, Betty was injured. Her job then was to climb out

on a high ledge and scoop up the shattered glass, so that chunks of it wouldn't

fall on the people in the street below. In the course of doing that, she cut a

finger.

…

Betty was fire-watching the night the doodlebugs first came

over London. The doodlebugs and the rockets that came over later were

nerve-wracking weapons, which the British felt were not quite fair.

"It was the inhumanness of the V-weapons that got most

people, I think," Betty said.

I

reviewed the novel here

early this year.

Monday, August 12, 2019

Sneak preview, FM36: Barbara Noble, The House Opposite (1943)

From

novelist Connie Willis's introduction:

I dislike most novels written about the Blitz. Most authors get the details, or worse, the

attitudes of the time wrong, and the stories they tell are melodramatic and

over-the-top, as if they concluded the Blitz wasn’t dramatic enough on its own.

I can only think of two movies and two

books which, till now, have gotten the particulars, the tone, and the story of

the Blitz right. The movies are 1987’s Hope and Glory and 2016’s Their Finest, and the books are Rumer

Godden’s An Episode of Sparrows and

Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair. And now, The

House Opposite.

I

wrote here

recently about how over-the-moon I was that one of my favorite authors, Connie

Willis, author of the breathtaking Blackout

and All Clear, had agreed to write

the introduction for our reprint of one of my favorite World War II novels (I

reviewed it here).

So you may imagine how I felt after reading the above passage. Words just

can't.

She

goes on to explain:

The

House Opposite, which is not only set in the Blitz, but is about

the Blitz and what it was like to be an ordinary person living through an

extraordinary time, working and eating and sleeping, making friends and growing

up and experiencing heartbreak, while all the time waiting for the ax to fall.

Noble captured that feeling so

perfectly that, as I read The House

Opposite, I found my heart pounding during even the quietest of

scenes: Elizabeth eating dinner in a

restaurant with her lover, Owen walking through the park late at night,

Elizabeth checking on a ward full of sleeping patients. Knowing that at any moment everyone—and

everything—could be blown apart.

Which eventually happens. But not at all in the way you expect, and so

casually that at first you don’t realize it’s happened—or how much damage was

sustained.

And

to a large extent contemporary critics recognized the value of Barbara Noble's

meticulous portrayal. Even the slightly snarky reviewer for the Guardian had to acknowledge the

documentary value:

The story of a married business man's liaison with his

secretary ... is of no importance, but this novel has positive value as a

faithful record of London life during blitz. It is factual, selective, accurate

in detail of event and behaviour. It is a notable feat of novelist's reporting.

Others

didn't give the sense that their praise was being reluctantly pried from their

typewriters, with the Times of India

calling it "the most satisfying picture yet of what life in London was

like during those hectic months." And Noble's book clearly struck a

personal chord with the review from the Sunday

Graphic, who said:

Finally, to confound those who imagine that there is only one

kind of "woman novelist" turning out standardised products, I draw

attention to The House Opposite...

...

The bombing of London forms an intermittent background to the

tale, and I cannot remember any book which so convincingly renders the

disordered, keyed-up tragedy and comedy of the blitz period so convincingly.

I read it while my own windows were rattling to gunfire; just

enough to awaken old memories. And every word rang true.

Saturday, August 10, 2019

Sneak preview, FM35: MARJORIE WILENSKI, Table Two (1942)

With

her usual brilliance as a researcher, Elizabeth Crawford provides, in her

introduction to our reprint of Marjorie Wilenski's only novel, an intriguing and

poignant glimpse of the author's early life:

Marjorie Isola Harland (1889-1965) was born in Kensington,

London, the elder daughter of Wilson Harland, an engineer, and his wife, Marie.

Her younger sister, Eileen, was born in 1893. Other details of Marjorie’s life

are infuriatingly sketchy. The papers filed by both parents in a long-drawn-out

case for judicial separation suggest that in her early years Marjorie witnessed

many upsetting scenes in the family home, her mother citing in lurid detail

numerous instances of her husband’s drunken violence and swearing. By 1902 the

couple had separated, Robert Harland returning to live with his mother in

Brixton while Marie retained custody of her daughters.

In 1907 the three were living at 37 Dorset Square, Marylebone

when Eileen died, aged only 14. The house is large and it may be that Marie

took in lodgers, although the female American singer and three Austrian

businessmen staying there on the night of the 1911 census are described as

‘visitors’ rather than boarders. Nothing else is known of Marjorie’s early

years other than that she was clearly well-schooled for she graduated from

Bedford College in 1911 with a 2nd class degree in history. Three

years later, on 5 August 1914, she married Reginald Howard Wilenski (1887-1975)

at Kensington Registry Office.

I

had previously known that she married Reginald Wilenski, a well-known art

historian, but absolutely nothing else, so this glimpse of what was surely at times a difficult childhood is

wonderful to have. And although the bitter, unmarried Elsie is clearly front

and center in the novel, she is obviously not, as one might have expected in a

first novel, a self-portrait.

Elizabeth

also sums up the novel, which I reviewed here

in 2016, far better than I did:

We first meet Table Two at lunchtime on 2 September 1940 in

the Ministry of Foreign Information, which Marjorie Wilenski places on the edge

of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, as Elsie and Anne watch an aerial dogfight high in the

‘deep blue sky’. At this time ‘no-one in London was then expecting air-raids’

but five days later everything changed. On 7 September the women have their

first experience of the Blitz, night-time bombing that was to dominate life

through the autumn. They, like other Londoners, become used to sleeping in

shelters and rising the next morning to ‘gape and gaze at the great craters in

the streets – [which] by Friday were just a familiar and tiresome obstruction

to traffic; there were too many other things to think of...’ But this cataclysm

is merely a background to the bickering and jousting for position around Table

Two when it is revealed that a new Deputy Language Supervisor will soon be

required.

An

understated but for once not very snarky notice of the novel in the Guardian put it this way:

They were an awkward squad, the women qualified chiefly by

residence abroad to act as translators in the Ministry of Foreign Intelligence,

and the professional women, office broken, had their proper scorn of amateurs. Table Two ... does some delicately

malicious character-drawing. Contrasted are the comedy of a lost document and a

pleasant love-story among air raids. Individuals in this group of women are

well differentiated, and it all seems quietly truthful, but had that Ministry

no canteen?

Finally,

Elizabeth also points out the most tantalizing mention of the novel:

Table Two was published in

the autumn of 1942 by Faber and Faber, the firm that since the 1920s had been

Reginald Wilenski’s publisher. It was widely reviewed and in addition we are

blessed with a view of it in the hands of a reader. For in May 1943 a copy

accompanied Barbara Pym as she waited in the queue for her Women’s Royal Naval

Service medical. She later wrote that ‘I read my novel Table Two by Marjorie Wilenski (obviously about the Censorship)’.

Alas, she offered no further comment.

Now, I ask you, would

it have been too much to ask that Pym might have added an adjective in there

somewhere ("I happily read" or "my delightful novel" or

"by the wonderful Marjorie Wilenski"). For all the gushing that she

did about frustrated love affairs, one might have thought one adjective could

be spared!

Wednesday, August 7, 2019

Sneak preview, FM34: ROMILLY CAVAN, Beneath the Visiting Moon (1940)

From

author Charlotte Moore's fascinating introduction:

Romilly Cavan was born

Isabelle Wilson in July 1914, on the very eve of the First World War. Her

mother, Desemea Wilson, produced thirty gloriously-jacketed romantic novels

under the pseudonym Diana Patrick, and when Isabelle began to write she also

adopted a pseudonym, "Cavan" perhaps in homage to her Irish heritage.

Her first novel, Heron, was published

when she was only twenty-one. At the launch party she met the literary

journalist Eric Hiscock, pronounced Hiscoe. They married six years later, by

which time she had written five more novels, of which Beneath The Visiting Moon, Evening

Standard Book of the Month, would be the last. Eric Hiscock claimed that

the wartime paper shortage was the reason Romilly gave up novels for plays.

Encouraged by Noel Coward, she wrote twelve.

She is a shadowy

figure. An early dust-jacket photograph shows thin, fine-boned intensity. Eric

described her as "dark Irish, very secretive"; she wouldn't let him

read anything she'd written until it was finished. She aimed high, and was

jealously competitive with other female authors. She couldn't stand to have

Edna O'Brien mentioned, said Eric, wouldn't allow her books over the threshold—but

after Romilly's death (from cancer, aged 61) he opened a cupboard and found

O'Brien's complete works concealed within. Perfectionism, as much as the paper

shortage, may have prematurely ended her novel-writing career.

Wonderful details, and I'm sure Charlotte is dead-on, but I might put a

more positive spin on things and suggest that, having achieved perfection with this novel, she may have felt a bit "I came, I saw, I conquered" and simply moved on to other challenges.

But

if you're afraid I'm overstating (and see here

for my original giddy review back in 2016), here's a sampling from the New York Times review of the book:

But, quite apart from wartime implications, what a delightful

little world it is Miss Cavan has created and how truly representative of the

time and the circumstances! One does not know whether to admire more the skill

with which the story is told from the adolescent viewpoint or the sly quietness

with which the elders' share in the cosmos is revealed.

It

can't be often that Times reviewers

resort to exclamation marks...

In

the Observer, no lesser figure than

novelist L. P. Hartley reviewed the book, slightly condescending perhaps but

enthusiastic nevertheless:

The pattern of Miss Romilly Cavan's long story is almost

negligible; nothing happens, and Sarah is too romantic and too young for us to

take her troubles very seriously [this from the author of The Go-Between?!?!]. But the detail is enchanting. Seldom do we

find minds so sensitive to the nuance of an idea, spirits so responsive to fine

shades of joy and sorrow. Facetiousness is the author's danger, but it is a

danger she runs over and over again to come back with some prize of truth or

fancy deliciously expressed.

But

the best summing up of all (and the first time, to my knowledge, that one of

our reprints has garnered a comparison with Virginia Woolf—not to mention Dodie

Smith!) comes from Charlotte's intro:

Beneath the Visiting Moon's surface

sparkle illuminates sombre depths. Lonely, unfulfilled adults, traumatised

children, and, most convincingly of

all, girls on the exhausting treadmill

of adolescence are created by Romilly Cavan with something of Dodie Smith's

lightness of touch, something of Virginia Woolf's sense of human tragedy. The

combination leaves us sharing Elisabeth's feeling that "all, (with the exception

of the world) was well with the world". Cavan's achievement is the very

essence of bittersweet.

Beneath the Visiting Moon is available in both e-book and paperback formats from Dean Street Press, released August 5, 2019.

Monday, August 5, 2019

Sneak preview, FM33 - Josephine Kamm, Peace, Perfect Peace (1947)

From

Eileen Kamm's wonderfully informative introduction to her mother-in-law's

novel:

She lived in London all her days, fascinated by the

interactions of city life, talking to her friends and to strangers she met at the

bus stop, and relishing the sense, during the period before and after the

second World War, of living at the hub of crucial events and witnessing social

upheavals unimaginable in the rather staid world into which she had been born.

Although the 1930s, when she did voluntary work with Jewish refugees and became

aware that religious persecution was not consigned to history nor Britain

immune from invasion, were an unsettling decade, it was in her nature to get on

with things. When war broke out in 1939 she joined the Ministry of Information

as a senior officer and pamphlet writer and had her flat bombed, as well as

publishing several novels for adults, of which Peace, Perfect Peace was penultimate.

I

noted in my review of the novel here

how invaluable it is as a detailed record of life in the immediate postwar

period, and Eileen expresses that far more eloquently than I did:

The close examination of what mercifully was to prove a

temporary world, with its clothing coupons, communal soup kitchens

euphemistically rebranded as ‘British Restaurants’, trains crowded with

homecoming soldiers and people tired yet optimistic of better times to come, is

sometimes poignant, and often wryly comic. It is history to us, but written

without the distorted nostalgia of distant memory. What we hear in Peace, Perfect Peace is the voice of a

lively young woman with an observant eye, experiencing that world every day.

As

with so many of the treasures from this period, there were some slightly

condescending reviews. After summing up the plot, the Guardian noted:

A comedy of contrivances ensues, common sense prevails, and

after a ladies' battle domestic peace is made. A small, good-humoured novel

handles the children with discretion.

The

Observer also stressed the supposedly

feminine themes, though perhaps a housewife somewhere can explain what he

means, as I can't quite decipher it:

Josephine Kamm dwells mercilessly on post-war discomfort, but

offsets the gloom with some happy dialogue and character-drawing. She is at her

best with the Woman; and every housewife will know whom I mean by that.

Thanks

very much, but I'll take Eileen's own summing up of the novel's womanly

concerns:

The characters, especially the women, are fully realised in

their faults as well as strengths; Peace,

Perfect Peace is, in a quiet way, a feminist novel...

Happily

there were also more enthusiastic contemporary reviewers, as evidenced by the

below, from the back cover of Kamm's subsequent novel, Come, Draw This Curtain.

Peace, Perfect Peace is available in

both e-book and paperback formats from Dean Street Press, released August 5,

2019.

Saturday, August 3, 2019

Sneak preview, FM32: VERILY ANDERSON, Spam Tomorrow (1956)

From novelist, children's author, and journalist Rachel

Anderson's introduction to her mother's memoir:

In 1954, in an

emotionally charged farewell editorial for The

Townsend, she wrote, ‘The war took so much from us that we grew to accept

deprivations almost without feeling. We lost friends, we lost our homes, we

lost whole ways of life..… (yet) we learned that, even in the parting of death,

something of the spirit is left behind on earth, something that we had perhaps

not known to exist in the living person, something that had lain dormant as the

hidden seeds of the willow-herb in the sooty City of London.’

A bit later, Rachel poignantly but inspiringly

describes Verily's reaction to her loss of eyesight, which is just the

positive, make-the-best-of-things sort of attitude one would expect having read

her memoirs:

As Verily’s eye-sight

began to fade, her piano was moved next to her bedroom to be more easily

reached and she took to dictating her work, leaving her family to correct it.

On being registered blind, she insisted, with typical positivity, how delighted

she was that at last she qualified to be trained for a guide-dog. She then

dictated an article for The Author (Society

of Authors journal) discussing how Milton might have adapted to having a canine

carer.

When

I posted about Spam Tomorrow earlier

this year, I also got a lovely comment from another of Verily's daughters,

author Janie Hampton (one of the women behind the wonderful History Girls blog). I hope

she won't mind if I share it again here so that more readers can enjoy it:

I'm one of Verily Anderson's 4 daughters, I wasn't born until

her 3rd book 'Our Square'. We all enjoyed seeing this, and the good news is

that Spam Tomorrow is being republished by Dean Street Press on 5 August 2019.

Verily was very proud that the Imperial War Museum held a copy of Spam

Tomorrow, where it's been used by many WWII researchers. 'Mummy Vincent' was

Nicholas's mother Noel, one of Verily's best & oldest friends, a lovely

calm woman. Kate was indeed Joyce Grenfell, in 'Scrambled Eggs for Christmas'.

None of us were her actual god-children, but she was like a fairy godmother to

us, passing on her stage clothes for us to cut up, and secretly buying us a

car, house etc. Twenty years after her death, I edited her letters, and wrote

her biography for John Murray publisher. I think 'Beware of Children' was

called ' No Kidding' in USA - after the film made by the Carry On... film

people.

From

Verily's Guardian obituary in 2010

(see here):

[H]er breakthrough as a writer came in

1956, at the age of 41, when she published Spam Tomorrow, a deft and frequently

uproarious account of her wartime experiences on the home front. Critics hailed

it as a new kind of memoir, one of the first to explore the lives of women

in wartime.

Before the success of Spam Tomorrow,

she led a life that was colourful but frequently impecunious. Born in

Edgbaston, Birmingham, the fourth of five children of the Rev Rosslyn Bruce and

his wife Rachel (nee Gurney), Verily was always certain that she wanted to be a

writer. As children, she and her brothers edited and wrote a nursery

magazine which they called the News of the World. Verily's haphazard schooling

ranged from a few years at Edgbaston high school for girls to being taught

at home by her mother, to a brief and unsuccessful stint at the Royal College

of Music in London. She said she worked at "100 different jobs"

(including writing advertising copy, illustrating sweet papers and working as a

chauffeur) before the outbreak of the second world war, when she enlisted with

the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, on the grounds that if there were going to be a

war, it would be "less frightening to be in the middle

of things".

And

finally, at another point in her introduction, Rachel drops in this little

tidbit:

From the age of nine, she

kept a daily diary, of which there remain 142 volumes, all marked “Strictly

Private”. These were never intended for public reading, let alone publication.

Oh

dear. What one wouldn't give to get hold

of one or two of those volumes!

Spam Tomorrow is available in

both e-book and paperback formats from Dean Street Press, released August 5,

2019.

Thursday, August 1, 2019

Sneak preview, FM30 & FM31 - CAROLA OMAN, Nothing to Report (1940) & Somewhere in England (1943)

“Lady Lenanton, last Friday I eloped and married your niece.”

With that telephone conversation Carola Oman

(1897-1978) entered my life more forcefully than before as the aunt of my wife,

the designer Julia Trevelyan Oman

Thus

begins art historian, museum director, and diarist Sir Roy Strong's

introduction to our new editions of Oman's wartime comedies, which I reviewed

early this year here

and here.

Sir Roy goes on:

Much of her childhood was spent in Frewin Hall, Oxford Wychwood

School , Oxford

...

She wrote during a period when, for women of that class,

servants were a given and ‘work’ in the sense of what happened after 1945 was

totally foreign to them. Right until the very end Bride Hall depended on a cook

and a butler-chauffeur. The world of Bloomsbury

would have been also totally alien to her as indeed what we now categorise as

that of the ‘bright young things’ and the smart set of the twenties and

thirties.

And

yet, in some of her early novels from the 1920s (which I posted about

here just last week), some of Oman's most incisive and realistic portrayals are of

young people who are, at the least, close approximations of "bright young

things," a sign that she was a conscientious observer even of those whose

experiences so widely differed from hers.

I

also have a post coming soon with wonderful photos and recollections by Carola

Oman's grandniece Elisabeth Stuart, but I can't resist including a snippet

here:

I knew her well from the 1950's to

1970's when she lived in considerable style with a cook and a butler unlike

anyone else we knew! We were very much on our best behaviour when we were

with her. She had a lovely panelled study in her Jacobean manorhouse where

she would write. She had a keen sense of her responsibilities and was a

governor of several local schools besides being a trustee of a handful of

national museums and galleries, particularly those relating to subjects where

she had written a major biography (for example, the National Maritime Museum

because of her biography about Nelson: her most important work).

Finally, I've always loved how Nicola Beauman and

Persephone highlight how male-centric critics looked down their noses at many

of the books today's readers love the most, so I thought I'd share my own

examples.

A short review of Nothing

to Report from the Observer,

though entirely back-handed in the praise it offers, would have perversely sold

me on the book even if I'd never heard of it:

the tale of a spinster lady's round of

interests, friendships, and endurances just before and early in the present

war. Story not much; characters recognisably genteel and county; but delicious

fun for the wise and gentle everywhere.

And a review of Somewhere

in England from the Sydney Morning

Herald, similarly dismissive of the book's focus on everyday trivialities, makes me feel sure I wouldn't care for this

critic's idea of a "soundly-constructed novel":

This is a group of contemporary

English portraits rather than a soundly constructed novel. It bears the formal

outline of a novel in that there are two or three continuous, lightly-sketched

love interests and the tenuous thread of Pippa Johnston's venture into war-time

nursing. The man interest of the book lies, however, in the author's ability to

look at people objectively and often with amusement. The background is a

typical English village, and the usual characters are on the stage: the Lady of

the Manor, the Vicar, the Matron and staff of the local military hospital, and

the natives. All of them are very capably handled.

"Somewhere in England" will

appeal to women with a love and knowledge of rural village life.

Well,

indeed.

Nothing to Report and Somewhere in England are available in

both e-book and paperback formats from Dean Street Press, released August 5,

2019.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

NOTE: The comment function on Blogger is notoriously cranky. If you're having problems, try selecting "Name/URL" or "Anonymous" from the "Comment as" drop-down (be sure to "sign" your comment, though, so I know who dropped by). Some people also find it easier using a browser like Firefox or Chrome instead of Internet Explorer.

But it can still be a pain, and if you can't get any of that to work, please email me at furrowed.middlebrow@gmail.com. I do want to hear from you!

But it can still be a pain, and if you can't get any of that to work, please email me at furrowed.middlebrow@gmail.com. I do want to hear from you!