What an up-and-down kind of reading year it has been (never mind the kind of year it's been in the news!), but ultimately what a productive and enjoyable one. At times this year, I was, I confess, lagging a bit, motivation-wise, but that all changed with our trip to England in October, and our time at the British Library and the Bodleian. You may have noticed my reinvigorated reading since then, and there's certainly more to come. I'm also well aware that we're overdue for an announcement of upcoming FM titles—our next batch has been delayed a bit, but our announcement should (finally!) be coming soon.

As always, I wanted to end the year by looking back at the highlights. My actual FM Dozen always (with one tiny cheat this year, but one which fits well thematically) focuses on my blog-specific reading for the year, but I like to mention a few highlights that were either non-blog-related or just didn't quite make the cut. This was, as always, a challenging year to narrow down to a dozen.

I had quite a splurge of mystery reading this year, after a long period of not reading them much. Particularly during our October trip itself, I read one after another. Since I don't regularly blog about mysteries, they're a restful retreat for me—no making notes, or thinking of clever things to say about them, just pure readerly pleasure. It was during our trip that I properly discovered EDMUND CRISPIN, with whom I have been passionately involved ever since. If you like a bit of intellectual zaniness in your mysteries, Crispin is your man (though I know many of you discovered him long ago). I also read a slew of GLADYS MITCHELL both before and during our trip, and she provided particular inspiration with her focus on stone circles in The Dancing Druids (1948) and The Whispering Knights (1980). And I very much enjoyed CAROL CARNAC's (i.e. EDITH CAROLINE RIVETT, who also wrote as E.C.R. LORAC) Crossed Skis (1952), which combines a murder plot with a group of cheerful folks on holiday in the Alps.

An embarrassing confession re my mystery reading: A few years ago, I wrote about reading Agatha Christie's Passenger to Frankfurt (spoiler alert: I didn't enjoy it), which I thought was the very last of Christie's novels that I hadn't read. Then, a few weeks ago, organizing my books and my database, I made the shocking discovery that there was another Christie I had missed. A few weeks passed, and as we've been relaxing over the holidays, I decided to treat myself to one last unread Christie. In due course, yesterday I finished Towards Zero (not her best, but not bad, and an interesting conceit), only to realize as I was nearly finished that it seemed a bit too familiar. I double-checked my database, and reader, I read the wrong book. In the ensuing weeks, I had got confused between two novels featuring Superintendant Battle. On the bright side, however, this means I still have my first read of The Secret of Chimneys to look forward to!

Further outside the realm of my blog, when Andy and I both got covid at the beginning of July, I found myself reading (and loving) LAURENCE STERNE's classic, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (1767). Covid brain clearly did unusual things to me. I also discovered American MAX EWING's brilliantly campy Going Somewhere (1934), and was saddened to learn he committed suicide the same year. Finally, one of my few reads this year of a book actually published in 2022, SELBY WYNN SCHWARTZ's After Sappho (2022), about modernist lesbians (and surely, by today's definitions, at least a couple of trans men) and the worlds they created, was gorgeous and inspiring and added considerably to my TBR list.

But enough name-dropping of those who didn't make the Dozen…

12) AUSTIN LEE, Miss Hogg and the Dead Dean (1958)

First up, my slight cheat. Including a male author is breaking my own rules, but I recently read the last two Miss Hogg mysteries that I hadn't read before and enjoyed them so much I couldn't resist. All nine of them are delightful, silly fun, and the first three were reprinted by Greyladies (here's hoping for more?). Not for the humdrum mystery fan, as the puzzles are no great shakes, but I have a feeling some of you would enjoy them for the characters and silliness.

11) SYBIL BOLITHO (as SYBIL RYALL), A Fiddle for Eighteen Pence (1927)

Two young women on a road trip through France, with sightseeing, periodic car trouble, run-ins with local residents, and occasional personality conflicts—not to mention a young man who just keeps popping up. A fun bit of virtual travel from the early days of cross-country road trips.

10) OONA H. BALL, Barbara Goes to Oxford (1907)

More charming virtual travel, and appropriate inspiration for our own stay in Oxford, this is the addictive fictional diary of a well-to-do Irishwoman's three weeks in the city with a friend, meeting extraordinarily friendly people who show them all the best spots. Largely a cheerful travelogue, there's also just a touch of romance…

9) ISOBEL STRACHEY, Suzanna (1956)

From very early in the year, this Strachey novel about a young woman trying to escape being defined by men is sometimes messy and uncomfortable, but has stayed with me throughout the year. It also reminds me that I must get back to reading more of her fascinating work.

8) KATHLEEN MACKENZIE, The Starke Sisters (1963)

Pure silliness about three sisters in the 1960s forced by their imperious great-grandmother to live according to Edwardian norms. This book and its two sequels were marketed as children's books, but both the humor and the descriptions of clothes seem more calculated to please adult readers.

7) ROSE ALLATINI (as EUNICE BUCKLEY), Family from Vienna (1941)

Any 1941 novel focused on a well-to-do Jewish family, some of British nationality, others refugees from Austria following the Anschluss, forcibly reunited in London, is bound to have some uncomfortable moments in view of the horrors that were to follow, but Allatini manages to produce a delightful family comedy, albeit with dark edges, from these materials. I'm ashamed to say that though I have managed to get hold of Allatini's two succeeding novels dealing with the same characters, I haven't yet got round to reading them.

6) JOYCE DENNYS, Economy Must Be Our Watchword (1932)

I've got a review coming up of this one, so for now I will just give a grateful thanks to Simon Thomas, who was willing to share his copy of this vanishingly rare title so I could read it. Stay tuned for more.

|

| Thank you to my faithful Fairy Godmother for this wonderful cover image! |

5) ANN STAFFORD & JANE OLIVER, Cook Wanted (1933)

I discovered this sequel to Handheld Press's delightful reprint Business as Usual entirely by accident, but loved it all the more as a result. Following that novel's heroine into the complications of married life, it's just as much fun as its predecessor, and now my Fairy Godmother has provided a scan of the irresistible dustjacket!

4) NOEL STREATFEILD (as SUSAN SCARLETT), Sally-Ann (1939)

It's hard to believe that it was only early in 2022 that I was reading some of Noel Streatfeild's frolicsome Susan Scarlett romances for the first time. This was one of the last I read, and if forced at gunpoint to choose my favorite of the twelve, I think this might just be the one.

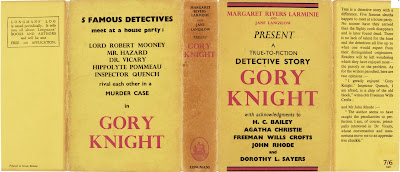

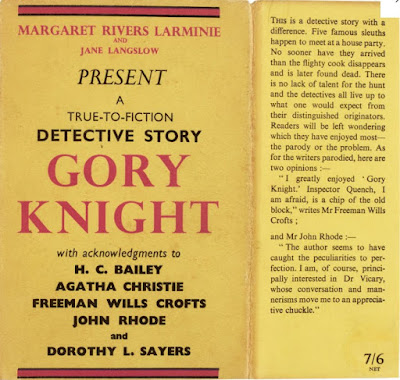

3) MARGARET RIVERS LARMINIE & JANE LANGSLOW, Gory Knight (1937)

One of two products of our England trip on this year's Dozen. I waited for years for someone to reprint this Murder by Death-like parody of Golden Age mysteries, and then decided to fetch it myself at the British Library. The parody versions of Hercule Poirot and Lord Peter Wimsey are particularly chuckle-inducing, and it's all energetic fun, even if the solution won't light any fires for die-hard puzzlers.

2) DOROTHY LAMBERT, All I Desire (1936)

My favorite Dorothy Lambert so far, not even excluding Much Dithering, which is really saying something. An author of torrid romances retreats to a quiet English village, only to find that her the skeletons in her closet, in the form of not one but two figures from her scandalous past, are waiting there for her. It's pure delight, despite its hideously inappropriate title.

|

| One of many illustrations not used in the books |

1) JOYCE DENNYS, The Henrietta Letters (director's cut) (1939-1954)

I'm cheating here a bit too as far as my usual rules go. I generally only allow one book per author in my Dozen, but rules are made to be broken (and I could say that this is technically not "a book"). What could possibly have been more exciting this year than my discovery that the 1980s volumes of Henrietta letters, Henrietta's War and Henrietta Sees It Through, contained less than half of the existing letters Dennys wrote for The Sketch during (and after!) World War II. I'm planning to put together a proper post about this soon, but suffice it to say that most of the material left out of the books is just as funny and charming as what was included!

And that's that for another year! Stay tuned for more new reviews coming along soon—as well as that long-awaited announcement of new FM titles coming, we now think, in April of 2023.

Happy New Year to all of you!

%20-%20A%20Fiddle%20for%20Eighteenpence%20cover.jpg)

%20front%20cover.jpg)

%20cover.jpg)

.jpg)