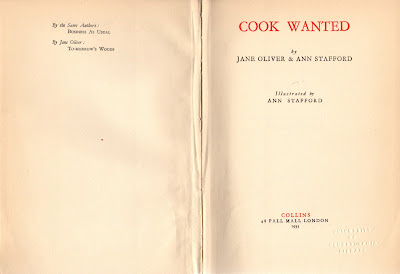

SPOILER ALERT (sort of, vaguely): As many of you undoubtedly know, a wonderful book called Business as Usual by Ann Stafford and Jane Oliver has been reprinted in the past couple of years by Handheld Press (see here). It's the completely irresistible tale of Hilary Fane, who, engaged to an unbearable prig who can't marry for another year, decides to take that year to support herself in London, and finds work in a London department store. Her diplomacy and practical thinking (rather than her clerical ability, which leaves a considerable amount to be desired) catch the attention of management—rather unrealistically quickly—and she advances at breathtaking speed in her career. (One feels that if other events hadn't intervened, she would have been running the department store by the end of her second year.) Along the way, there's loads of fascinating and entertaining detail about the running of the library and book department of the store and their quirky inhabitants. Do absolutely read that book, if you haven't already, but none of this is the spoiler. The spoiler is that I put in an interlibrary loan for another Stafford & Oliver novel, Cook Wanted, apparently published the same year as Business as Usual, primarily because it was one of the only of their books that I could get hold of, and discovered only after its arrival that it is in fact a sequel, of all delightful things, to BAU. For that reason, it's impossible to write about it without taking for granted the conclusion of the earlier book—though in all fairness you'd have to be a pretty willfully obtuse reader not to see that ending coming by about a quarter of the way into the novel anyway.

Still, be warned!

I went back to dinner with Aunt Bertha afterwards and asked her weakly if she didn't find voluntary work quite exhausting. She said: "Well, Hilary darling, between ourselves, I sometimes think it isn't the work so much as the Workers." And we would have champagne, she said, because it did Pick you Up. And after dinner I felt much better, but just as I was thinking blissfully of getting to bed really early she suddenly began to burrow in her bag, and sent her maid to search all her pockets and attache-cases and alternative handbags for her Diary. She was quite hysterical about it. "There are Things in it, my dear," she said dramatically. I asked: "What Things?" and she said: "All the names of the people on my committees. And I'm bad at remembering about people, so I just marked them with T for tiresome, S for stupid, D for dull and B for bad-tempered." So I said soothingly that that would be quite all right for nobody would ever guess what she meant.

"Oh, yes, they will," said poor Aunt Bertha, "I felt it would be so much more business-like if I put the code in too. Just in case ... "

Although published the same year as Business as Usual, Cook Wanted takes place several years later (the first book ends in 1932, so presumably we're at least to 1938 here if one were being boringly numerical). Hilary Fane is now Hilary Grant, and business has taken her loving husband Michael to Canada for six months, leaving her home alone with just their 5-year-old son Adam, her good friend Mary Meldon, who comes to stay during Michael's absence, her various servants (including several troublesome cooks, which provide the loose structure of the book), and of course her social activist Aunt Bertha, "addicted to committees". Also providing lively difficulties are Curtis-Fitton, Adam's hoity-toity nurse, Rutherford Worsthorne, a preeminent archaeologist met briefly in BAU and here figuring more prominently with his bull terrier, and Basil Rainford, Hilary's former fiancé, who is somewhat regretting having allowed Hilary to get away (though he's still as much of a prig as ever).

Apart from dealing with various entertainingly chaotic domestic staffing crises, Hilary in this volume gets pulled into Aunt Bertha's world—to serve as Honorary Secretary of the Federated Women Citizens, and further in when when she's drafted, despite her best efforts, to a subcommittee:

But when one of the least hard-bitten and hand-woven members told me that her sub-committee was drafting resolutions on Overtime Among Office Workers (Female) I was tempted—it's still a sore subject with me. And when she mentioned the value of my personal experience at Everyman's and wondered if I realised that under Clause CCCXVIII of the new Bill millions of typists would be working night as well as day, I took fire and followed to the slaughter. As a result I had a Sub-Committee for the Regulation of Women's Working Hours from ten till lunch-time and the Central, All Purposes, goddam-awful Committee Meeting from two o'clock till five-fifteen.

Things become more complicated when Hilary is able to snag Mary the job as editor of the organization's paper, only to find her soon after instigating a strike by the group's own typists, whom they are ironically exploiting mercilessly. Then Basil catches her at a weak moment in Michael's absence, Adam has a health scare, and she and Mary hit the rocks over Hilary's attempts to throw Mary together with Rutherford Worsthorne. Oh, and she has an unexpected encounter with another supporting cast member of BAU as well.

It's all completely irresistibly entertaining, and like BAU it's accompanied by Ann Stafford's charming line drawings, used to illustrate her letters to Michael in Canada and to her family in Edinburgh, which are the primary content of the novel, with occasional memoranda and other insertions. If it's perhaps slightly more uneven than the first book, as most sequels are, it was still a pleasure to read, and I'm so glad my random ILL request happened across it.

Unfortunately, based on a Twitter comment from Kate at Handheld when I tweeted about finding the book, it seems that they have no intention of reprinting this one. She suggested that there was a sort of deal-breaker in it. I didn't notice anything major along those lines, though there are some minor irritants, like when Hilary is seeking a school for Adam and Aunt Bertha refers to "backward cases" as being "catching". Not atypical for the time, but still grating to our ears. There might be something else that went over my head, however.

Be that as it may, there are two more amusing and/or interesting passages I'll point out. One, purely for giggles, follows a jaunt Hilary and Mary take into the country, going for a long horseback ride, only to discover after resting at lunch that they are, shall we see, a bit out of practice:

After that the weather improved and we left the pub after lunch for a Long Walk. But we found that we hadn't counted on the after-effects of our first ride for years. We were both just birpling. Like two old, old bodies. I said that I was sure it couldn't be just stiffness: it must be Rheumatic Fever. And Mary said, surely not, but that it was certainly very odd and we would look up the symptoms in Black's MEDICAL ADVISER as soon as we got back to London if rigor mortis didn't set in first.

(BTW, I am now resigned to feeling exactly this way the day after each and every workout, no matter how frequently I exercise. I remember the good old days when I was only sore when I hadn't worked out for a long time, but those days are sadly in the past. Now it's 24/7 sore.)

The other passage is a striking one from a meeting Hilary has with Lady Agnes, the elderly founder of the Federated Women Citizens:

After that Lady Agnes kept us both for dinner and talked about Hunger-Striking and insides of Prisons and point-to-points in Ireland and religious revivals in Wales and Vice-Regality in India until we felt that Commonweal House was a very small pea on a very large drum. As intended. Bless her. I asked her, as I've always wanted to ask one of the Militants, how so many really brilliant women came to do things like setting pillar-boxes on fire and chaining themselves to railings.

And Lady Agnes said: "Well, my dear, when you give men a series of reasoned logical arguments, and they pat you on the shoulder and say 'Run along, little woman; government's a man's job,' you just naturally put out your tongue at them. Besides, it's the only way of getting their attention."

It seems frankly as though we may need to start smashing windows and setting pillar-boxes alight again…

I did manage, by the way, to snag one other Ann Stafford novel via interlibrary loan, a postwar title called Near Paradise (1946), and I've apparently just inadvertently purchased two more (I was just seeing what was available—truly I was!). And I might have laid hands on the one remaining copy I found for sale of her third novel with Oliver, Cuckoo in June, which looks delectable but does not appear to continue Hilary's story. (Perhaps just as well, because at the rate Hilary was conquering realms, a couple more volumes about her would surely have led to her being Prime Minister during World War II instead of Churchill!)

But first and foremost I am also going to finally get round to reading Stafford's Silver Street (1935), which Greyladies reprinted a few years ago and which appears amazingly to still be available from them (see here). As usual, Shirley Neilson was the trailblazer who first discovered Stafford's charms, so I can only assume in advance that Silver Street is a particular treasure.

As for Oliver, I had come across a wartime novel of hers, The Hour of the Angel (1942), a few years back, read just a bit, and quietly returned it to the library. Her husband, John Llewellyn Rhys, whose name has been immortalized by the literary prize she created in his honor, had died only the year before, and the book was very much about her grief and also her interest in spiritualism, which apparently only increased in later years. Not to my own particular taste, so I think I may stick with Stafford or the two's early books together under their own names (they later wrote billions of Mills & Boon romances together under the name Joan Blair, but I'm not sure I'll need to delve too deeply into those either—okay, perhaps not billions, but quite a lot of them). But if you know of a Jane Oliver novel you really recommend (or a good Stafford, for that matter), do let me know. I'm on the prowl, as always.

I enjoyed Business as Usual, being a bookish person (reminded a bit of Emily Kimbrough's time in Marshall Field's bookstore, in Through Charley's Door). Do wish I could read Cook Wanted.

ReplyDeleteThat's true, there is a bit of a Kimbrough-ish feel about it!

DeleteA very interesting and enjoyable review relating to a very interesting and enjoyable set of books. And I love the cover art to the reissue of Business as Usual.

ReplyDeleteWish I could read them both.

Jerri

I was lucky enough to find the reissue of Business As Usual in eBook format from my public library via the Hoopla app. Very much enjoying it so far.

ReplyDeleteJerri

Glad you're enjoying, Jerri.

DeleteIntriguing. I love Business as Usual and have had a chance to read Cuckoo in June, which is thoroughly enjoyable but not of the same quality as Business as Usual (I'd still happily read it again if someone wanted to reissue it though! It's great for inspiring travel dreams). I've tried one of the Joan Blair romances and, based on my miniscule sample size, you are safe to skip these!

ReplyDeleteI'm sure I'll have more reviews to come. Haven't read Cuckoo yet, but looking forward to it and have read one more I didn't mention above because I didn't think there was a chance of getting hold of it!

DeleteA children's novel, Queen Most Fair, by Jane Oliver, about Mary Queen of Scots trying to escape from captivity on an island. It captivated me as a child and I think I still have a grubby pb somewhere. Of course, it might not be a children's book to be read with any pleasure by an adult.

ReplyDeleteInteresting. Thanks for the recommendation!

Delete