My lovely Greyladies edition of Murder

Judy sat staring out of the railway carriage window. Of course there was a war on, but could any train that was trying at all really dawdle the way this one was doing?

Now that I've got started reading and writing about Susan Scarlett (see here), I find that I can't stop, and in light of world events in the past few days it seems wise not to stop.

I read these two recently in a continuing desire to avoid any contact with reality. If I wouldn't say that these two are quite as good overall as Clothes-Pegs and The Man in the Dark, which I wrote about last time, they were still marvelously effective at getting my mind off the news.

Murder While You Work is one of two Susan Scarletts that are explicitly set during wartime (along with Summer Pudding, which I wrote about here ages ago). It's also Streatfeild's one attempt (to my knowledge) at a more or less straightforward murder mystery. So it might seem odd to say that this might have been the perfect Susan Scarlett novel if not for the damned murders, but that is indeed how I felt about it.

Our heroine, Judy Rest, arrives in the village of Pinlock to take up her new work in a munitions factory. On the train, she makes the acquaintance of Nick Parsons when he rescues her dropped lipstick (quite valuable under wartime circumstances), who, it turns out after the two engage in some extremely careless talk, is also engaged in top secret work at the same factory. Nick, the only surviving son of the formidable Lady Parsons, whom we shall meet and come to love later on ("I was the child who was too delicate to live. And now look at the damn thing. The sole survivor."), warns Judy that he's heard disturbing things about her new billet, wherein a suspicious death has recently occurred. Da-da-da-DUM.

Judy is admirably unflappable, however (if a complete dolt when it comes to romance, as we shall see), and becomes fond of elderly, recently-widowed (in peculiar circumstances) Mrs. Former and her daughter Rose, though distinctly less fond of Clara Roal, Mrs. Former's niece, who is angry and disgruntled and more than a bit shady. Clara's son Desmond is a problem too, an eight-year-old with developmental or mental health issues that manifest in his apparently nonsensical speech and tendency toward cruelty.

And then more murders occur. Unfortunately.

Judy is charming and intelligent and capable (except in regard to love, but that works itself out, of course), Nick is witty and brave and appropriately admires Judy for her capacities as well as her looks, and the wartime setting allows Streatfeild to pack the book with fascinating detail from her own experiences. All of that I loved, and to use my favorite expression for this type of reading, the pages turned themselves. I devoured it as readily as I am capable of inhaling a tub of cookies and cream ice cream, and I assure you that my capabilities in that area are impressive.

What, then, could possibly be wrong? It's just that the murder plot is purely an annoying interruption of an otherwise entertaining frolic. It's perfectly obvious from the beginning who the murderer is, it's the why and how that are (slightly) mysterious, and the victims are (breaking the golden rule of cozy mysteries) likable and harmless. One victim we only hear of, as he is dead when the novel opens, but the next is a sweet, charming supporting character that we have grown to like. Not to mention a dog… [cringe emoji]

If only instead of a boring murderer there might have been just an annoying person that Judy and Nick had to maneuver around. One gets the sense Streatfeild wanted to show off her knowledge of psychological issues by portraying a psychopath, but I could have lived without that display. There's also Desmond, whose portrayal is perhaps accurate from a psychological standpoint but is quite insensitive by today's standards (including a single use of the "r" word, along with various other only slightly less grating descriptions). His behavior is monstrous, but one can quite see how he got there and feel sad for his grotesque neglect.

Those reservations aside, however, the novel is an absolute delight. Nick's plucky mother, Lady Parsons, in herself makes up for most of the negatives, as for example in discussing her faithful housekeeper's fortunate age:

Dibble was my personal maid before the war, but now she does everything. Up till the war was declared Dibble went on from year to year being thirty-nine, and then suddenly, when registration started, she came to me one morning and laid her birth certificate on my desk and there she was fifty-two. Of course I said nothing about the thirty-nine, I was too thankful. I just said, 'Isn't that splendid, Dibble!' and she said, 'Yes, my lady,' and we've never mentioned it since."

The tidbits and interactions in the munitions factory are also a delight, as when Judy is instructed about maintaining the proper rhythm with her lathe ("The girls in this group say that 'White Christmas' just swings it nicely"). So while the unfortunate murders may keep this from being my favorite Susan Scarlett, it still lands fairly high up in the pile.

Next up:

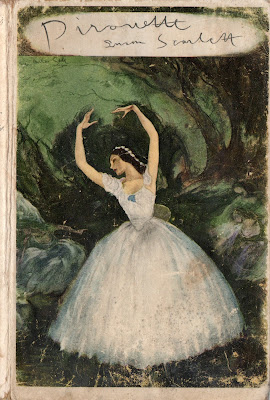

|

| The rather lush original cover (never mind the mildew stains) |

"I've been watching you. Ever since you came to my school I've said to myself, 'There's something in that child which one day may, if she works, flower.' I'm now going to give you a chance to show the world what you can do. When I give a chance to one of my dancers I'm giving into their hands my reputation and the reputation of my school and of my ballet. Dancing is not, as with some of the other arts, a matter of short inspiration and quick effects; dancing is a vocation. A girl whom I choose to star as much gives her life to dancing as a novice entering a nunnery gives her life to religion."

Pirouette might land a little further down the pile for me—it's beginning to seem to me that the later Susan Scarlett novels have more angst and less cheerful energy than the early ones—and its focus on an 18-year-old ballet dancer on the cusp of stardom gives it a bit more of a feel of Streatfeild's children's books too, though it does contain a more or less effective romantic element. But of course center stage here is the ballet interest, and Streatfeild's intricate knowledge of a ballet company and of the dreams and frustrations of young dancers (and of the tyrannical instructors and directors who threaten to derail their lives). That's what makes this a page-turner despite it's unremarkable leading lady.

Judith Nell has been working and striving for success all her life, though this proves to have been as much due to her mother's own frustrated ambitions and her ceaseless pressure on Judith as to Judith's own wishes. Love in the Mist, the final Susan Scarlett novel, which I haven't yet reviewed, has a silly, misguided mother, no doubt, but Pirouette has one that should be promptly smothered with a pillow. Streatfeild's interest in obsessive and problematic personalities sometimes leads her to create exaggerated caricatures instead of characters, and Olive is a mother only a, er, masochist could love. Obsessed with Judith's success in a field she aspired to, Olive is at the point of completely ignoring her other children—Peter, having difficulty adjusting to life after serving in the war, and young Tim, in danger of getting involved in a gang because he feels neglected, not to mention her husband John, who has humored her in her obsessive attention to Judith but is now reaching the end of his rope.

|

| Original back cover |

Of course, Judith falls in love with Paul, the brother of a fellow dancer, who is heading off to a good job in Rhodesia in a few months and wants to take her with him—just as she gets her big break in a starring role.

Some readers will cringe a bit at the book's ultimate attitude on the question of career vs. marriage and children, but of course no one can fairly expect radical political attitudes from a romance novel (though, expected or not, they have been known to creep in). As Paul sees it, "It was a damn' silly life, the ballet, sure to let her down in the end. Nobody wanted a wife with a career; it would be a far better thing if she could be persuaded to throw the whole thing up." And the irony of her father saying that Judith must make up her own mind about things as he advises Paul how to manipulate her is worthy of a cynical laugh.

But despite that, the tale has some irresistible elements. There's a delightful scene in which Prudence and Olga, two of the ballet company's stars, are deliciously catty to each other in a restaurant in front of their respective romantic interests. And one can't help but wonder if Streatfeild is making use of personal experience in the scene in which young Nadia, Paul's sister, having trained all her life for stardom but now heartbreakingly grown too tall, gives Madame Tania a brilliant telling-off that she won't soon forget. Those moments are well worth the bits of handwringing between Judith and Paul and Olive, and a plot that one can see coming a mile off.

Since I now have all the Susan Scarlett books waiting patiently on my shelves, and since the world news sure as hell isn't getting any better, I imagine I'll be reading more of them soon. Here's hoping they're all as entertaining as the ones I've read, even if none of them are likely to astonish me with their plot twists!