Okay, after only one of my four posts talking about new authors added to my main list, I am already bored with alphabetical order. I've already divided the 60 authors into four equal groups based on alpha order, but within those groups I'm going to be a loose cannon and take them in whatever order strikes my fancy.

I've actually already reviewed a book by HILDA HEWETT, and will have more reviews or at least mentions coming up. See my review of So Early One Morning here, where I also talk about coming across her in the latest issue of The Scribbler and the productive transatlantic book talk that resulted. I believe I can safely say that Hewett is a wildly uneven author, but that when she's good she's very good. Sadly, unlike Mae West, when she's bad she is definitely not better.

Meanwhile, how often will I be able to write here that I've already published books by the niece of an author being added to my list? Pretty sure it will never happen again, in fact, but indeed, one of the things that came out of Elizabeth Crawford's wonderful introduction to the six Elizabeth Fair novels published as Furrowed Middlebrow titles by Dean Street Press is that her aunt, BETH ELLIS, also deserves to be here. She seems to have achieved the most fame for her travel book, An English Girl's First Impressions of Burmah (1899), which was described by one source as "one of the funniest travel books ever written." That book is available (in the U.S. at least), for free downloading from Google Books. A few years later she began to publish novels, most of which were historical romance. She had published seven (1903-1912) by the time she tragically died in childbirth in 1913. I'm going to have to sample her work, if only because the thought of a cross between Elizabeth Fair and Georgette Heyer is completely irresistible.

There's another familial connection with GILLIAN GOLDEN, who turns out to be the daughter of children's author Dorothy Dennison. Among Dennison's last published works were two in a series of family tales called the "Courtney Chronicles." I don't have details, but it seems that Dennison wrote the first, Spotlight on Penelope (1958), and third, Call Me Jacqueline (1958), while her daughter wrote the second, Over to Paul (1958), and fourth, Bouquet for Susan (1958). Have those of you with an interest in children's books ever come across any of these?

Among this batch of newbies are two hitherto unknown (to me) mystery writers. ELIZABETH GILL first came to my attention when Dean Street announced their reprinting of all three of her novels—Strange Holiday (1929, aka The Crime Coast), What Dread Hand? (1932), and Crime de Luxe (1933). She received acclaim for her work, but sadly died at the age of 32. See Curtis Evans's introduction to the Dean Street editions for interesting details about her.

Gill

was probably as obscure, before Dean Street's rediscovery of her, as KATHERINE

FIELD still is. In contrast to all the authors whose careers were

interrupted or stopped altogether by World War II, all three of Field's novels—Disappearance

of a Niece (1941), The Two-Five to Mardon (1942), and Murder to Follow (1944)—appeared during

the war. According to a Goodreads review, the second of these, at least, seems to make use of wartime themes.

She lived until 1957, but published nothing else that we know of after the war

ended.

A couple of my fellow bloggers have already discovered CELIA FURSE, who published only a single novel. The Visiting Moon (1956), which relates a young girl's visit to a large English country house over the Christmas holidays early in the 19th century. Barb at Leaves & Pages reviewed it here, and Ali at Heavenali reviewed it here. It seems to be one of those books that walk the line between memoir and fiction, but it seems to be fictionalized enough to qualify Furse for my list.

I wonder if there could be another blogger rediscovery in the offing for MARY GRIGS? It's probably a long shot, but a review in the Bookman of her debut novel, Bid Her Awake (1930), has me intrigued:

There is

dignity here, and beauty as well. It is the story of a conflict between two

sisters, the imperious Alix and the shy suddenly transfigured Susan, and the

latter's brief excursion into love. It is an air for muted strings that Miss

Grigs gives us, with little dancing notes of gaiety in it, and a sombre theme.

So quietly is it done that the insensitive reader may fail to perceive the artistry

with which it is composed; though he cannot fail to be charmed by the effect so

subtly created.

Oh,

dear. A future interlibrary loan request? Grigs went on to write four more

novels and two children's books, and she wrote a column in the Farmer's

Weekly under the pen name Mary Day.

KIT HIGSON came to my list via the back of the impossibly obscure Lorna Lewis title Tea and Hot Bombs, which I reviewed a while back. I was rather disconcerted by one of Higson's titles listed under "Stories for Girls". Cop Shooter (1958) is one of those books that likely would be retitled if it were published today, though looking into it a bit more deeply, I discovered that it's about a dog named Cop, owned by one Simon Shooter. Higson (Kit turned out to be short for "Kitty") wrote more than two dozen works of fiction in all, for both children and adults.

Accusations

of racism against an author are often a bit challenging to establish, what with

the ever-changing meanings of words, figures of speech, and attitudes. (See Huckleberry Finn for reams and reams of

critical controversy about whether Twain was extraordinarily enlightened,

virulently racist, or some balance of the two—I tend to plump for the last,

though the book is probably the great

American novel regardless.) I came across this again in researching the

largely-forgotten ANN FIELDING, who published three novels in the 1940s

and 1950s. In her scholarly work, Political

and Social Issues in British Women’s Fiction, 1928–1968, Elizabeth Maslen (whose

work on World War II fiction I greatly admire) notes that Fielding's third

novel, Ashanti Blood (1952), about

gold miners in Africa, is "[a] particularly repellent example of racist

and class stereotypes" and adds that "Fielding represents the extreme of inbuilt prejudice." It was

striking, then, to find that John Betjeman, in a contemporary review of

Fielding's second novel, The Noxious Weed

(1951), about a British family becoming tobacco growers in Africa, went out of

his way to praise Fielding's portrayal of the growth of racism and

insensitivity in a family initially horrifed by British treatment of the locals.

Of course, the two novels could be quite different in tone, and Betjeman was

writing from the sensibility of at least a half century earlier than Maslen,

but it was interesting to see the contrast in reactions to a single author—perhaps

not all that different from those about Twain.

Regardless,

I have now added Fielding's first

novel to my "tentative TBR" list. The Mayfair Squatters (1945) is about a diverse group of people who take

over an empty London house during World War II. No word yet on race or class

portrayals in that one.

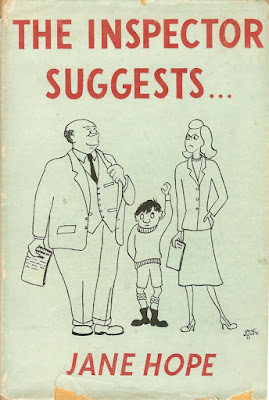

JANE HOPE was suggested for my list by another reader of this blog, David Redd. She may just barely belong on my list, having written a number of humorous books about the British education system, but it's hard to imagine that a title like The Inspector Suggests, or, How Not to Inhibit a Child (1951), however much it might be based on Hope's own experiences, isn't at least somewhat fictionalized. I debated about adding her to the list, but decided, as usual, to err on the side of inclusivity. I wonder if One Term at Utopia: Pages from the Diary of Jane Hope (1950) might belong on my Grownup School Story List? And for that matter Happy Event: A Humorous Account of a Child's First Year of Life (1957) could be the perfect vintage gift for a parent-to-be.

And now, since I've taken these authors out of order and picked and chose all the more interesting tidbits, I come to the last five authors, about whom I know nothing exciting or interesting. ALDGATE EAST (real name Amy Adelaide Ebdell) published a single novel, Darrimore (1939). DOROTHY MARK FISK wrote several science-oriented non-fiction works for children, as well as a play and one novel—The Golden Isle (1930)—though details are entirely lacking.

There's a similar dearth of knowledge about JANE GILBERT, who wrote two novels—Man Is For Woman Made (1940) and Take My Youth (1941)—and about MARJORIE HOGARTH, who wrote three—Marriage for Two (1938), The Eyes of a Fool (1939), and The Intruder (1940).

And finally, I do at least

know that ELIZABETH COOMBE HARRIS's

three dozen or so books were mostly Christian in theme and apparently included

fiction for both adults and children.

So, these last few authors aside, this batch of new authors contains a lot more potential than the first one. I count six or seven that I might have to track down and read, and one of them I already have. How about you?

So, these last few authors aside, this batch of new authors contains a lot more potential than the first one. I count six or seven that I might have to track down and read, and one of them I already have. How about you?

I might have to try Mary Grigs' The Yellow Ct, only because of Sparky, my big orange cat - the cover art could have been him as a baby.

ReplyDeleteI'm sure people have picked books for worse reasons than this - and besides, I have YOUR recommendation!

Tom

It's a great cover, isn't it? I've sometimes been pleasantly surprised by judging books by their covers, so you never know!

DeleteAldgate East is a station on London Underground, on the boundary of the City and Whitechapel, which suggests where Amy Adelaide Ebdell set her book.

ReplyDeleteWonderful tidbit. So any reader familiar with London would have known it was a pseudonym. Thanks for sharing that.

DeleteAs always love the cover art. I was sure I owned something by Elizabeth Gill, but can't find it. The ones from Dean Street Press are on my personal wish list for when I can afford and have time to read some.

ReplyDeleteI am interested in the comments about Jane Gilbert. The cover art by her is Imps and Angles, not listed as one of the two novels she wrote. Is that a children's book, not a novel? The cover looks interesting and it is "illustrated", but inquiring minds want to know more.

Jerri

You're right, Jerri, I was a bit careless there. Imps and Angels was Gilbert's third and final work of fiction, a children's book which, I now discover, is set during the time of the construction of Lincoln Cathedral. According to the Saturday Review when it first appeared: "There are midnight pranks in the bell tower and strolling players, the annual Miracle Play and the every-day life of Hugh and his family. The story is touched with a humor that makes it

Deleteseem contemporary." Hmmmm, you may have just added yet another title to my TBR list...

Those three Katherine Field novels are all WWII-related, with the earlier pair (Disappearance of a Niece and Two-Five to Mardon) loosely linked, in that several of the characters from the first reappear in the second, together with the recurring Scotland Yard inspector, who's in all three. Niece and Mardon involve the uncovering of separate 5th-column plots and are set roughly in their years of publication, '41 and '42, I believe, whereas (perhaps confusingly) Field's 1944 novel, Murder to Follow, jumps back to '39 and concerns the misappropriation of a baby amid the flood of evacuee children then taking place. In that chaos, the baby (not to say the plot) is murder to follow. By the way, I'm glad you include a biographical date for Katherine Field, as it makes her seem more like a real person than what I'd supposed when I first read these, which is that she was maybe just another nom de plume for someone like Cecil Street, given the humdrum narrative style of these mysteries – with each chapter unveiling a new clue to be endlessly chewed over and theorized about by the detective and his colleagues.

ReplyDeleteGrant Hurlock

Thank you for the additional information about these, Grant. Always very happy to have you share some of your wealth of knowledge of wartime fiction! Yes, her name would have been a plausible pseudonym, but John traced her as Katherine Mary Ida Field, 1875-26 Aug 1957. Based on your comments, I'd guess the books are not must-reads? Though the setting of the third in the midst of chaotic evacuations sounds like it could have some interesting period detail?

DeleteI didn't really mean humdrum as a negative criticism. It's a legitimate subgenre – see Curtis Evans's book on the subject. And I'm happy to put up with the talkiness of the form for the sake of the mundane details of everyday life these novels provide. A writer like Street is particularly valuable for having written so much during the war years. He turned out a couple of dozen 80,000-word novels dated 1939 to 1945, when other authors were producing maybe one book every year or two or else falling entirely silent for the duration. Some of his, e.g., Dead of the Night, Night Exercise, They Watched by Night, and The Fourth Bomb focus explicitly on Home Guard and ARP operations as arenas for homicide and its detection. Anyway, I think you might enjoy all three of those Katherine Field titles. Do try Murder to Follow, though, as it transpires mainly in an English village to which its female protagonist escapes; not only that, she also takes work there as a teacher in the local school to earn her keep, so this book could also perhaps find a place in your list of school-related stories.

ReplyDeleteGrant Hurlock

Oh look, Jane Hope! It must be about fifty years since I have thought of her. She used to make me laugh a lot.

ReplyDelete