Clearly, it's about time for me to retire my original Hopeless Wish List, as its hopelessness has happily been dwindling away! Today, I get to cross off yet another title, thanks to the extraordinary kindness of a fellow blogger.

Those

of you who follow Simon's fascinating blog at Stuck-in-a-Book may have noticed his

post on this book last month, which had been a gift to him a few years

ago. If you did, you may also have read

at the end of that post of his intent to "pay it forward" by

forwarding the book—the only Olivier title which had seemed truly hopeless to

track down—across the Atlantic to me.

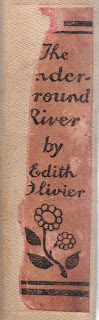

The

book arrived just a few days ago, and it's an adorable little thing—as you can

see. So, in short, thanks very much to

Simon for so generously making this post possible, and for allowing me to cross

another title off my Hopeless Wish List.

Of

course, not being known for my self control, I immediately tossed aside the

other books I was reading and dived right in.

And once started, I couldn't stop reading, because Olivier's quirky

charm is evident throughout. You can

sense it right away in the opening paragraph:

This story begins with a cross aunt; and if she hadn't been so

cross there would have been no story to tell. Aunts now are generally not so

cross as they used to be. In the old days, they were very alarming people indeed.

But now, when they cut their hair short like their nephews, and cut their

skirts short like their nieces, they don't seem much older than the children

themselves, and play with them as if they were all the same age. Aunt Lucinda

was not really the children's aunt; she was their great-aunt, which means that

she was the aunt of their father, so she was very old, and was allowed to be

cross, as the old aunts were.

Tony

and Dinda, whose parents are in India, are sent to stay with their distinctly

cross Aunt Lucinda—who, among other things, raps the homesick Dinda across the

knuckles with a ruler and scoffs at the notion of magic, thus establishing her

credentials as the novel's villainess.

Not

long after their arrival, a dowser arrives to find a good location for a well

on Aunt Lucinda's land, and the children discover 1) that Dinda herself is a

dowser, and 2) that an underground river runs right under their aunt's

property. They then hatch a plan to find

the river and ride it to the sea, where they will stowaway on a ship for India

and return to their parents.

Naturally,

it wouldn't be a proper children's book if it didn't require a considerable

suspension of disbelief, but I have to say that I found the fantasy of the

underground river—and the surprising inhabitants the children discover there—to

be quite effective (and fans of Jeanne DuPrau's Ember books might find Olivier's tale a worthy precursor). A few months ago a

reader commented that he had managed to buy a copy of the book for his mother, who

remembered it as one of her favorites as a child. And I can quite see how this would be. It seems like the kind of fantasy which, encountered in childhood, would linger in one's mind.

(I would say that it's surprising that the

book has never been reprinted, but I fear I'm starting to sound like a broken

record.)

The

children's initial descent into the underworld is rather vivid and (as Simon

pointed out in his review) a bit humorous:

It was a very mysterious beginning to the voyage. There was

not a gleam of light. The children felt their way with their hands along the

river banks, holding the boat off from the shore while the current carried them

along. Now and again their faces were brushed by invisible flying

creatures-bats or beetles or unknown birds-which flew against them in the dark.

Dinda clung to her hat, for the servants had told her that if a bat got into

her hair it could never get out till her head was shaved, and she did not like

the thought of one flying in now, and having to stay there for the whole of the

dark voyage.

After a time they felt hungry, but they found it was very

difficult to eat their meal in the dark. They each had a knife and fork, but

they had never guessed how hard it would be to cut slices for themselves off a sirloin

of beef, with no butler to carve, no carving-knife and fork to carve with, and

no light to carve by.

If

only they had thought to bring along a butler on their adventures!

It

turns out there is a whole civilization underground, extending well back into

history and supported by Robin Hood-esque peddlers who steal supplies from

above and sell them to the under-inhabitants "in exchange for stones and

pebbles and suchlike useless things which were found under the earth"—i.e. gemstones, presumably? The children encounter Mother Caldey, who

came underground years before because the waters help her gout; are nearly

enslaved for a year and a day at the Tinker's Camp; and meet dwarfs and fairies

and bootleggers.

Mother

Caldey is my favorite of these, as she is a rather charming—if bone lazy—good-natured

old women who soaks her feet and waits for visitors to come along and tell her

stories. Though it must be acknowledged

that were she alive today she would undoubtedly make a compelling episode of Hoarding:

Buried Alive:

The two children went into the cave. It was a vast place, and

its walls were like a great warehouse, packed with things. Near the door were

cups and saucers, hundreds of them, perhaps thousands. They were piled on

shelves one above the other, and more than half the cups had been put away

dirty. The others seemed never to have been used at all, and were mostly still

packed in the paper in which they came from the shop. The back of the cave was

stacked with blankets of all colours-red, white, grey, and brown-and they too

were piled in heaps to the very roof of the cave. The place smelt stuffy, but

it was warm and comfortable after the cold of the night before, and the

children wished they could have had some of Mother Caldey's blankets to cover

them through that shivering night.

I have

to admit that some small, anti-social, bone lazy part of myself identified just

a little with Mother Caldey, and I briefly flirted with an image of an idyllic

life of soaking my feet in the hot springs while leisurely perusing novels and

memoirs by little-known British women. But

then I realized that

the steam from the hot springs would wreak havoc on my books, and that

would certainly not do. So above ground I will stay.

I

imagine that grad school Scott could have made something rather psychoanalytic out of Mother Caldey's cavern next to a caldron, particularly in

view of its deeper, hidden depths:

So Tony and Dinda washed up, and then they set to work and

tidied the part of the cave which was nearest the door. They felt they could

not attempt to do anything with the back part. It was a confusion of things, half

hidden in the darkness—things that had been used and put away one behind the

other in a dirty heap. But Mother Caldey was delighted to see even a part of

her home made neater, and she said she hoped the children would stay a day or

two with her before they went on.

It all sounds a bit id-like? But fortunately

for us all, grad school Scott rarely rears his ponderous head these days, and blogger Scott is happy enough just picturing this bone

lazy crone (and, obviously, using the expression "bone lazy"

repeatedly) buying new dishes and clothes to keep from having to wash the old.

At any

rate, the book is really all great fun, and will no doubt be a periodic re-read

for me. It's also a wonderful little addition to Olivier's body of work. And I leave you for now with not

so much a funny ha-ha passage—since Olivier is known for her odd charm more

than her hilarity—but rather a funny unusual passage. How many children's books today (or, when it

comes down to it, ever) would present

two small children and a bootlegger's horde as follows?:

Tony hastily picked up two of the big fisherman's coats, and

taking a bottle of whisky which had been partly emptied, he hurried back to

Dinda with his booty. They were both still too occupied with their cold and

misery to ask themselves to whom these spoils belonged, or to fear that they

might suffer for having carried them off, but they both quickly took off their

wet and freezing clothes and wrapped themselves each in one of the thick, warm,

woolly coats. Then they both drank a few mouthfuls of the whisky. It was very

horrible and burning in the mouth, but it made them both feel marvelously warmer

when they had drunk it down, and now they could begin to look forward to the

future, and to discuss what they had better do next.

With an accompanying illustration, no less! I just

bet that they did feel marvelously

warmer after a few shots of whiskey!

Purely medicinal, of course. And

hey, this was the 1920s after all...

How lovely that you've read it already! It's got a much better home with you than me, and I'm so pleased that the internet can help unite books with their rightful owners :)

ReplyDeleteWhen I was doing research into Olivier, I read some letters she wrote to her publisher, and I believe she objected at length to the American publishers of this, as they wanted to take out the alcohol scene!

That's so interesting, Simon. Well, I suppose we were in the grip of Prohibition at the time. Interesting to know that Olivier felt so strongly about the scene, though. Regardless, the illustration was one of my favorites. I do envy you for your research on Olivier's letters and diaries!

DeleteOh the days when children got up to all sorts of danger and somehow made it to adulthood. So different from today when children are driven around the block to school. The bottom illustration made me laugh.

ReplyDeleteDon't plan a trip to England without stopping by to meet Simon, he's one of the friendliest people you will ever meet.

It's very true, Darlene. I imagine many of these adventure stories, of kids facing up to danger on their own, would be good medicine for oversheltered kids today.

DeleteAlas, our next trip is to Italy, so no England for a while. (Obviously, I don't mean "alas we're going to Italy," just "alas we won't be back in England for a year or two"!)

I have an early copy of the underground river. One of my favourite childhood books I have kept.

ReplyDelete