This post, about 13 more authors added to my main author list in my most recent update, is a bit of a catch-all. All of them are interesting in one way or another—either for their work or their connections to better known figures, but they don't have anything in particular in common with each other.

For example, I'm not certain I'll read any of JANE HUKK's three novels, all concerned to some extent with India, where she lived for more than a decade with her husband: Abdullah and His Two Strings (1926), about an Indian student at Edinburgh University who, though already married at home, falls in love with his landlady’s daughter; The Bridal Creeper (1928), in which “a young man marries out of his class, and repents in India, where he and his wife each seek suitable consolation”; and End of a Marriage (1935), about a World War I marriage between an Indian man and a Scottish woman, who vow never to meet again, but do, unexpectedly, under very different circumstances. But I thought some of you would like to know that, following her return from India, Hukk lived in Berwick. Her stepsister was none other than Anne HEPPLE, and in a 1929 interview Hepple said she was inspired to try her hand at writing because Hukk had been successful at it.

I've added LAURA WILDIG's only novel to my future British Library list. Pandora's Shocks (1927) is a farcical tale with supernatural elements, in which an impoverished scientist pays his rent by providing to his wealthy young landlady a “genie,” a man’s mind extracted from his body, with whom she has many adventures. Could there be shades of Miss Carter and the Ifrit there? Wildig was also a playwright and artist, and at least four of her plays were produced in London—Once Upon a Time (1919), Priscilla and the Profligate (1920), Punchinello (1924), and (after a considerable absence noted in the play’s reviews) The Boleyns (1951). Her other interesting tidbit is that she was part of an informal group known as The Launderers (see here), which also included a number of young actors and artists, as well as no fewer than three other authors from my list—a young Antonia White, Mary Grigs, and Naomi Jacob, the last of whom also appeared in one of Wildig’s plays.

You might think watching our idols come crashing down was a modern pastime fueled by social media, but DOROTHY BARTLAM might have something to say about that. She was a film actress and author of a single novel, Contrary-Wise (1931), about glamorous life in Devonshire, Paris, and London. She seems to have played supporting roles in little-known films, and given up acting on her 1933 marriage, so perhaps she hardly counts as an idol, but her subsequent publicity never fails to mention her celebrity status. In 1936, she was in the divorce courts with her first husband. On the 1939 England & Wales Register, she is divorced and gives her profession as “writer”—she may have published short fiction or articles, but no more novels. And in 1949, she was in the papers, referred to as “former film actress,” for driving under the influence.

Early (pre-marriage) pic of Gertrude Landa

I'm slightly obsessed with playwright, journalist, and novelist GERTRUDE LANDA. Much of her fiction was in collaboration with her husband, Myer Jack Landa, but her debut novel, The Case and the Cure (1901), about the romantic lives of two sisters, was a solo production. In 1908, she published a well-regarded anthology, Jewish Fairy Tales and Fables under her Aunt Naomi pseudonym. With her husband, she published four more novels, which all sound entertaining and unique. Jacob Across Jabbok (1933), which according to novelist Margaret Kennedy was an answer to the question “What does it mean to be a Jew?” She praised its good humour. Kitty Villareal (1934) was based on the true story of the life and adventures of the first Jewish peeress (see here). Chykel-Michael (1935) was widely marketed as the first truly humorous Jewish novel since Israel Zangwill's earlier work—a critic summed up "Chykel-Michael are two practical jokers of the ghetto, who find in their environment in free England an endless source of amusement and opportunity for good deeds.” And The Joy-Life (1937) deals with the unlikely friendship between a widowed “Scarlet Woman” and a pure and naïve country girl. Landa and her husband also collaborated on a number of plays, and played a significant role in encouraging British Jewish theatre. Landa was the sister of novelist Samuel Gordon and aunt of author Phyllis Gordon Demarest (included on my list). And, quite apart from her work, there is one more fascinating detail about Landa. In the annals of law, she is notable for the injunction she successfully obtained against the Jewish Chronicle, for which she had written using the Aunt Naomi pseudonym. Her legal action established that she had a right to the pseudonym she had created, and the magazine could not go on using it after her departure. The case was cited as precedent in numerous subsequent cases involving authors’ rights.

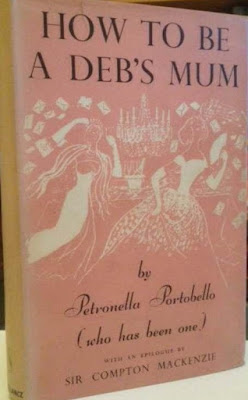

Biographer and novelist FLAVIA GIFFARD comes to my list thanks to an alert from Simon Thomas, though her name may not immediately ring any bells for him. She published three novels under three different names. As Flavia Giffard, she published Keep Thy Wife (1931), the tragic tale of a romance between an Englishwoman and a half-Indian, half-Irish man. After her marriage, as Flavia Anderson, she published Jezebel and the Dayspring (1949), a retelling of the story of the Phoenician princess. And under the amusing pseudonym Petronella Portobello, she published How to Be a Deb's Mum (1957, published in the U.S. as Mother of the Deb), an epistolary novel in the form of letters from the harried said mother to her friend, describing the mishaps of launching her daughter into high society. Its epilogue was contributed by Compton Mackenzie. It was the lattermost novel that Simon alerted me to, and I thank him for the heads up. She also published (as Flavia Anderson) two volumes of non-fiction—The Ancient Secret: In Search of the Holy Grail (1953) and The Rebel Emperor (1958), about the Taiping rebellion of the mid 19th century. She was also the great-niece of Elinor Glyn, another list entrant.

.jpg)

Image swiped from Mark's post at Wordwoodiana

I also owe thanks, this time to Mark Valentine who blogs at Wormwoodiana, for flagging GILLIAN EDWARDS for me. Her first novel, Sun of My Life (1951), has a man researching the life of a college acquaintance, a poet whom he has saved from suicide only to have him die soon after of pneumonia. Mark reviewed it here and compared its structure to Symons’ The Quest for Corvo. She didn’t publish again until The Road to Hell (1967), in which "a well-meaning man enlists the aid of the dark powers to bring prosperity to an unsophisticated village in the Mediterranean, and, in doing so, brings the village people all the ills of civilisation.” I Am Leo (1969) is about the downfall of an arrogant prince in Renaissance Italy, and Tower of Lions (1971), also set in that locale, features Giulio d’Este, imprisoned by the Borgias for 50 years due to a youthful indiscretion, reflecting on his life and times. Accidental Visitor (1974), set in the present, deals with an author living in isolation on an island, who must share his space for a time with a suicidal, recently-widowed woman. I could find no details about her final novel, Fatal Grace (1978). She also published three volumes about word origins—Uncumber and Pantaloon: Some Words with Stories (1968), Hogmanay and Tiffany: The Names of Feasts and Fasts (1970), and Hobgoblin and Sweet Puck: Fairy Names and Natures (1974).

There could be a substantial separate list of authors with some affiliation to Bloomsbury, and ANNA D. WHYTE would be included. Apart from anything else, she was one of the young women present at Newnham College for Virginia Woolf’s famous lecture there (as well as one by E. M. Forster). But her two novels were also published by the Hogarth Press, complete with Vanessa Bell covers. Change Your Sky (1935) is set among English folk escaping a dreary March in a pension in Florence, and how the improved climate affects their sensibilities. Lights Are Bright (1936) is about the adventures (including hurricane and earthquake) befalling a heroine in pursuit of the man she loves, and the new love she finds instead. Her writing was sometimes compared to Virginia Woolf, but there are indications that her own relationship with Woolf was ambivalent and that her early admiration may have faded with time. She was born and raised in New Zealand, but her parents were Scottish and she returned to England to attend Cambridge and seems to have remained for the rest of her life. She worked for the BBC during World War II, and in later years moved to Dorset with her family and managed Thomas Hardy’s birthplace near Dorchester for the National Trust.

On the subject of literary admirations, the first mention I came across of PAULINE MARRIAN noted that she was a great admirer of Dorothy Richardson while still quite young; the two were introduced in 1920 and they continued a friendship and correspondence through their lives. Marrian went on to publish two novels of her own. Under This Tree (1934) features a heroine struggling to break free from her old-fashioned home life—a reviewer noted, “This full-length sketch of a premature frump could easily have been shallow and spiteful, especially if the author had shown any signs of pertness. Actually, it is both satirical and sympathetic. Her Janet may be an appalling bore to her friends, but she is a joy to follow." Destruction's Reach (1935) deals with a painfully shy but nonetheless passionate woman, and her struggles to triumph in a stage career. She lived for a time in Hungary, and after World War II, she worked for the British Sailor’s Society.

Perhaps arguably belonging on a French version of this list, FRANCESCA CLAREMONT had close ties to Provence and presumably lived there at some time, but she gave her birth nation as England on U.S. immigration forms and lived mostly in England as an adult. She published poetry, a volume of children’s stories, and a biography of Catherine of Aragon (1939), as well as five novels. Magical Incense (1932), set partly in Germany, is about the difficulties of the three daughters of a country parson. Lost Paradise (1933), which seems to have received particular acclaim, is about a Frenchwoman, married to an Englishman, who puts her lush recollections of her old home into letters to her cousin. Turn Again, Ladies (1934) is about an embittered woman, widowed from an unhappy marriage, who must find a way forward with her daughter and a close friend. Dead Waters (1936) is a historical adventure set in Provence in 1288, in the time of the crusades, and The Shepherd's Tune (1960) is also set in Provence just before the outbreak of World War II, about a young shepherd who seems to cause strange disruptions among the locals. Claremont was a Montessori teacher for most of her life; following her husband’s death, she moved to Los Angeles and became a director of the teacher training institute there. Despite all this detail, however, I haven’t been able to trace her maiden name.

Farcical comedy can very easily go awry if an author is not very skilled in her handling, but I confess I'm a bit intrigued by NEVE SCARBOROUGH's two humorous novels. Pantechnicon (1934) has Ruritanian elements, though its setting is London—the dethroned king of a fictional country and his daughter take to working in a very unique department store. Shy Virginity (1935) features a parson’s wife who is determined to have a singing career; “the author handles subjects which Victorians treated as 'tabu' with a good deal less than Victorian reticence." Scarborough seems to have spent a fair amount of time in Scandinavia, and published Seldom Deer, or, Wheels Across Denmark (1936). In later years, she was active in social causes, particularly on behalf of girls with disabilities, including those caused by polio. Strangely, considering her local prominence, she seems to completely disappear from public records and newspapers after 1958, and I could locate no obituary.

It's always fun when a contemporary review hands me on a silver platter the essential clue to identify an author who might otherwise have proven a challenge. So I appreciate a 1958 review which says, of CLARE SIMON, "The author who writes under this name works by day in Hatchards and writes in the evenings. She is the daughter of Michael de la Bedoyere, editor of the Catholic Herald…" This led me easily to Sybil Clare de la Bédoyère (later De Boer), whose four novels received significant acclaim when they appeared. The Passionate Shepherd (1951), begun when the author was only seventeen, is about the love of a priest for a young woman. Oh, the Family! (1956) deals with a Sussex farm family, with a father who is none too good at farming and a mother doing her best to make a home. Bats with Baby Faces (1958) finds an Austrian WWII refugee trying to adapt to life in an English convent school. And Glass Partitions (1959) is about the love troubles of a young woman journalist. I have Bats waiting to be read…

I could perhaps have saved GLADYS ST JOHN LOE for my next post on mystery writers, since her final novel, Smoking Altars (1936) concerns the travails of a man who believes he has inherited a homicidal mania, but it doesn't sound exactly like it fits my mystery category either. Loe published four other novels and a story collection. Spilled Wine (1922) is about a young woman, ashamed of her lower class origins, who becomes a wildly successful author (and lover). In Beggar's Banquet (1923), a young typist inherits a thousand pounds and heads out to explore the world. The Door of Beyond (1926) has supernatural elements, with a hero who is possessed by a spiritual twin; he finds said twin embodied in a woman, only to have her spirit taken over by his dead wife. Meanwhile, I could almost believe that Who Feeds the Tiger (1935), which “keeps us perpetually amused by the local gossip and social taboos of the quiet, imaginary cathedral town of Glenchester,” and which was published as by “Eve St John Loe,” were by another author entirely, as it sounds quite different from her other work, but Gladys' middle name was Eve and library catalogues seem clear that it’s the same author. Her story collection was Dust of the Dawn and Other Stories (1922), and she also published a one act play, Sentence of Death (1930). Her husband was one Charles Edmund St John Loe, but a lingering mystery is where the "St John" came from. It’s not on his early records, nor do his father or grandfather ever seem to have used it at all. It’s possible that the couple simply adopted it at some point for its upper crust sound?

And actually, my last author, FRANCES LAYLAND-BARRATT, could also have appeared in my mystery writers post. But although Ann Kembal (1934), set in Manchester, was described as “a very unusual crime story of a successful murderess,” the rest seem more like melodrama, some with supernatural touches. She wrote six novels in all. I found no details about the first two, The Shadow of the Church (1886) and Doubts Are Traitors (1889), the latter subtitled "The Story of a Cornish Family," but Beatrix Cadell (1892) deals with a heroine with no formal schooling or religious background, who falls for an immoral schoolmaster. She published a story collection, The Queen and the Magicians and Other Stories (1900) and a volume of poetry (1914), but otherwise fell silent until the 1930s, when she published three novels in consecutive years, beginning with the aforementioned Ann Kembal. Lycanthia (1935) sounds quite a lot like horror, with a heroine “reared in an atmosphere of unhappiness and suspicion, and nursed by a female dedicated to the Devil … Strange happenings ensue, in which a huge wolf-like animal plays a terrible part.” Goodness. There's a copy available on Abe Books for a quite reasonable $10,000… And Joy Court (1936) plays on the old bugaboo about inherited insanity. I doubt I would have enjoyed having tea with Layland-Barratt: In 1922, she was quoted in the papers advocating strongly against allowing women into Cambridge, and indeed against higher education of women in general—“What is the good of being able to tackle Euclid if you don’t know how to cook a dinner?” Ahem.

%20-%20Jezebel%20and%20the%20Dayspring.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)