[For those of you not on Twitter, apologies for the radio silence the past couple of weeks. We were in New York and DC having a blast and forgetting all about our real world concerns. But I'm back now and nearly finished battling jetlag, and here's a review I wrote just before setting off and never got round to posting.]

During the last few days Francesca had begun to look unusually well, Vittoria unusually unwell—and, to Corinna's experienced and avid nostrils, the whole apartment reeked of approaching drama.

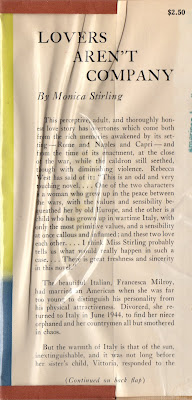

Of late (as you, dear readers, can readily attest, hopefully not regretfully) I’ve become more than a little infatuated with Monica Stirling. This is the fifth of her ten works of fiction (eight novels, two story collections) that I’ve reviewed, and it hurts me to say that this is the first time she’s disappointed me.

I might have purchased a second copy

of the book entirely for this photo

Lovers Aren’t Company is the story of Francesca Milroy, a native Italian who has lived in the U.S. since before the war, having married (then amicably divorced) an American, and who is now returning to Italy for the first time since the war ended. Upon her arrival, she finds that her sister Graziella, a famous singer with whom she had a sometimes tense relationship, has died just two months before of appendicitis. Graziella’s husband having been killed during the war, their 14-year-old daughter Vittoria is now an orphan, being cared for by the family’s ever-faithful—if rather prickly—servant Corinna.

Vittoria and Francesca immediately form a bond, but when they take a trip to Capri to visit Francesca’s friend Flavia, their relationship is strained. There, Francesca meets Jean-Claude, a French liaison officer devoted to helping those displaced by the war. Vittoria realizes, even before Francesca does, that romance is in the offing. Terrified of losing yet another person she loves, Vittoria falls in with two other children working with a shady American soldier selling goods on the black market. Things come to a head when Francesca is visiting London and Corinna wires her that Vittoria must surely be dead…

And although we deluded ourselves by paying tribute—horrible, hypocritical, abused wartime verb—to their sacrifice, it was not this that appealed to us but the fact they were outlaws. What would happen now: now that the resistance had come down from the mountains, up from underground, now it was no longer a myth with restorative properties, a tonic for night starvation, now heroes were become human beings—than which nothing is more disillusioning to the improperly developed imagination of other human beings—with personal faults, internecine quarrels, an intransigence developed in them by war and eager to feed on the peace?

Her characters, too, are for the most part vividly real, especially Vittoria and her young friend Giovanni, whose parents were killed in an air raid and who now half expects every scenario to end in disaster, as in this passage in which he watches a bride and groom emerge from a church and begins to imagine he can hear bombers approaching:

The church's somber entrance was brightened by the emergence of a solemn wraith in white muslin, her arm resting, in a histrionic demand for support, upon that of a smiling bridegroom dressed as if to achieve the closest possible resemblance to a black beetle. Momentarily isolated, like flies in amber, in the poetic banality of their situation, the young couple posed with grave compliance for the benefit of clicking cameras and the pleasure of clucking relatives.

…

Nearer and nearer came the sound, reminding Giovanni that no amount of joy could prevent bride and bridegroom being transformed, as others had been before them, into a small pile of jelly beneath a great pile of stone. Bomb damage, he thought: the words horribly fresh, vivid, substantial in his architecture-conscious imagination.

So what was my disappointment then? Well, unfortunately, what Stirling had not yet acquired when writing this novel was a way of writing about romantic love that wasn’t painfully sentimental and stilted. I’m pretty certain that I blushed during the main Francesca/Jean-Claude love scene, and it was neither because the scene was so graphic nor (I assure you) because I am a shrinking violet when it comes to such things. I was simply embarrassed for Striling that an editor had allowed such passages in print for the whole world to see.

Do I have an example, you ask? Oh yes, I certainly do! How about this?:

Quickly Francesca checked him by laying her hand over his. She wanted time to think. But having got it she found that the acquisition of time did not automatically bring her the power to think. She loved him and he did not love her and he did not love her and she loved him, and why think, why not just take the situation for what it's worth, but what is it worth?

"Francesca," he was saying, the long, soft name brief and sharp upon his foreign tongue, "Francesca oh Francesca ... "

"Jean-Claude," she answered, softening and lengthening the foreign vowels, "oh Jean-Claude, Jean-Claude ... "

Oh Monica, Monica … what were you thinking? And in the midst of my embarrassment I couldn’t help recalling that Stirling’s library cards from Shakespeare & Company in Paris in the very early days of the war have been shared online and reveal her taste for Hemingway (whom I also adore, against all odds), and noting yet again just how awful the Hemingway influence can be in authors who aren’t in fact Hemingway. He would surely have been tempted to challenge Stirling to a boxing match over this passage!

But that’s not all. Here’s another snippet just to be sure of leaving a bitter taste in your mouth:

So this is it this is it oh this she felt, and suddenly she remembered her beautiful mother, her handsome father, and their harvests of raised voices and slammed doors and brandished letters and she thought but it needn't be that way surely it needn't. And then she stopped thinking and remembering: because a cry that was almost a groan was dragged out of her, a cry of longing such as she had never known. Hearing it, Jean-Claude kissed her again and again and then took her, with the intense pleasure of a virile man who likes to possess without degrading by possessing.

I’m afraid that in this novel Stirling—in the immortal words of Bon Jovi—gives love a bad name.

However, onwards and upwards in my love for Stirling overall! This one might be a book I’ll only return to rarely, for its visions of postwar Italy, but having read four of her other titles from throughout her career, I’m reasonably confident that there are other excellent books still to come.

Of course, a weaker novel like this one, among an otherwise strong body of work, raises an interest dilemma. If, just for the sake of argument, we were to consider reprinting Monica Stirling as Furrowed Middlebrow books, should we include the weaker work in the interests of completeness, knowing that some readers will be disappointed? Or do we leave it out, knowing that some readers will then crave the one they can’t have (however unworthy I may think it of craving)? What do you think?

It’s these kinds of questions that keep me up at night…

(Actually, truth be told, they don’t. Very few things are able to keep me up at night—sleeping is one of the few things I do really well—but they do concern me now and then in my waking moments.)